In my previous blog post, I introduced MySQL’s transaction locking implementation, focusing on InnoDB’s locking process during an INSERT operation. This post will cover the locking processes for SELECT... FOR SHARE/UPDATE, UPDATE, and DELETE operations in InnoDB.

Why group these three operations together? Because they share very similar locking processes. All of them involve the SQL layer fetching data from InnoDB and applying transaction locks. The only difference is that, in the case of SELECT... FOR SHARE/UPDATE, once the SQL layer fetches the data and locks it, the statement is complete. However, with UPDATE and DELETE, after fetching and locking the data, the operation proceeds to either update or delete the data before writing it back to InnoDB. But when it comes to applying transaction locks, the process is the same. Before diving into the detailed locking process, it’s essential to introduce some background knowledge to facilitate a better understanding.

1. Essential Background Knowledge Before Diving Deeper

1.1 Interaction Between the SQL Layer and InnoDB

As we know, MySQL supports multiple storage engines, and InnoDB and NDB are just two of them. For a user SQL query, the SQL layer is responsible for parsing, optimization, generating the execution plan, and invoking the storage engine to perform data read/write operations. The storage engine handles low-level data management and operations, and the SQL layer interacts with the storage engine through interfaces to read and write data. Let’s take a few SQL queries as examples:

SELECT * FROM tbl WHERE ...

UPDATE tbl SET ... WHERE ...

DELETE FROM tbl WHERE ...

Question: If you were the designer of MySQL, how would you design the interface for the SQL layer to interact with the storage layer (e.g., InnoDB)?

To answer this, let’s first analyze the common characteristics of these three queries: They all generally involve using the WHERE condition to locate a matching record in InnoDB. For queries like WHERE unique_key = XXX, which perform exact lookups, the SQL layer can stop once it retrieves the matching record from InnoDB. However, for queries like WHERE unique_key > XXX or WHERE non_unique_key = XXX, the first record returned by InnoDB is usually just the starting point, and the SQL layer needs to traverse forward or backward to retrieve all records that match the WHERE condition. So, what kind of interface would be best suited for this operation?

The answer is an iterator. For instance, using the find() interface of an iterator to locate the starting record, and if further range scanning is needed, continuing with prev() or next() to fetch the previous or next record iteratively until the operation is complete.

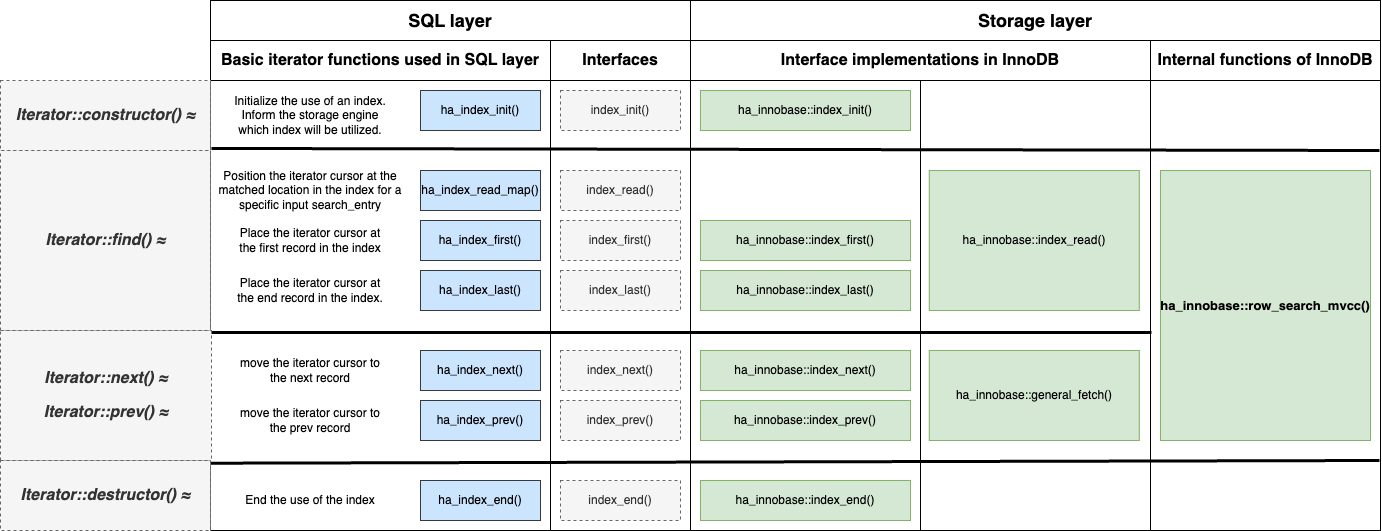

Indeed, MySQL defines its interface as an iterator, though the naming is slightly different, as shown below:

The blue section shows the fundamental functions used by the SQL layer to implement various high-level iterators (e.g., IndexRangeScanIterator). These functions include:

ha_index_init(): Informs InnoDB about which index will be read.ha_index_read_map(): Takes a specifiedsearch_entryand searches InnoDB, which is equivalent to the functionality of theIterator::find()we mentioned earlier.ha_index_first()andha_index_last(): Similar toha_index_read_map(), but instead of searching for a specifiedsearch_tuple, they retrieve the first or last record in the corresponding B+Tree index of InnoDB.ha_index_prev()andha_index_next(): These move the current position of the iterator to the previous or next record, respectively, from the current location in InnoDB, similar to theIterator::prev()andIterator::next()functions mentioned earlier.ha_index_end(): Handles cleanup work.

Note: These are not the only interfaces. There are many others like ha_rnd_prev() and ha_rnd_next(), which are declared in the SQL layer to scan non-ordered indexes (e.g., hash indexes). However, for InnoDB, the underlying implementation of ha_rnd_XXX() still calls index_XXX() because all InnoDB indexes are ordered.

The SQL layer has a very complex mechanism for reading data from InnoDB, with many high-level iterators defined. However, regardless of the complexity, they are all built on top of the basic functions introduced above.

Now, looking at the diagram again, shift your focus to the gray section on the right, which represents the interface between the SQL layer and InnoDB. The ha_XXX() functions mentioned earlier are implemented using these interfaces. For example, ha_index_read_map() calls the index_read() interface, which is declared in the SQL layer and implemented in InnoDB.

Moving further to the right, the green section shows InnoDB’s implementation of these interfaces. For instance, ha_innobase::index_read() corresponds to the implementation of the index_read() interface, while ha_innobase::general_fetch() implements the index_prev() and index_next() interfaces.

Finally, the functions used within InnoDB to implement these interfaces are shown, with one of the most important being ha_innobase::row_search_mvcc().

This function implements the index_read(), index_first(), and index_next() interfaces.

Therefore, ha_innobase::row_search_mvcc() will be the main focus of this blog post. It handles InnoDB’s data retrieval and locking process. Before delving into the specifics of row_search_mvcc(), there’s one more important topic to cover:

1.2 Parameters of These Interfaces

We’ve looked at the definitions of these interfaces and their corresponding implementation functions in InnoDB. There are some important parameters that need to be passed between them:

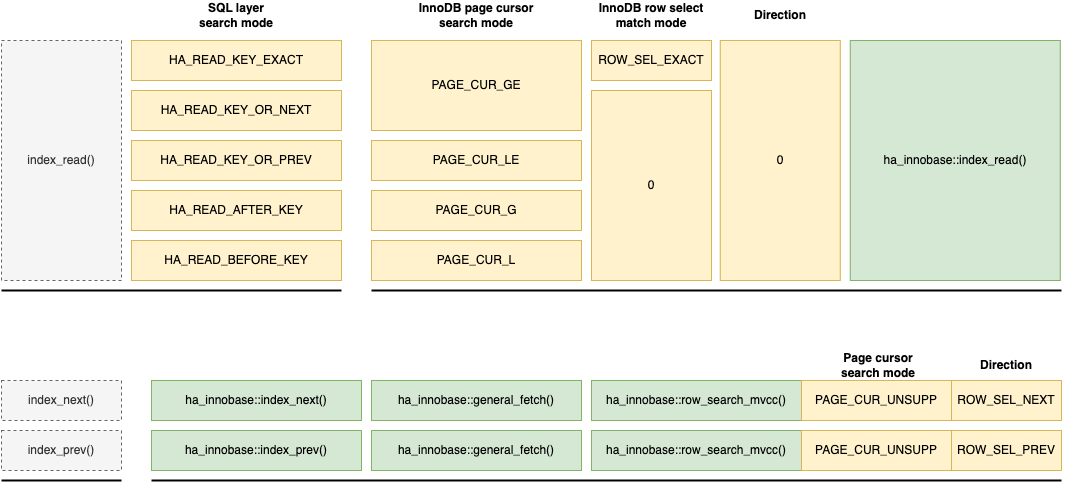

- For

index_read() -> innobase::index_read(), the first requirement is the specifiedsearch_tupleto look up. Then, there’s the search mode (<,<=,=,>=,>). Different search modes determine the exact position where InnoDB will locate the desired record. For example,< search_tuplewill locate the largest record in InnoDB that is less thansearch_tuple, while= search_tuplewill locate the largest record equal tosearch_tuple, and so on. This search mode represents where the SQL layer expects InnoDB to position the cursor. However, in InnoDB, records are stored in B+Trees—more precisely, within B+Tree pages. When InnoDB locates a specific record within a page, it uses its own defined search modes. Thus, when implementing these SQL layer interfaces, InnoDB must translate the SQL layer’s search mode into its own internal search mode. For example, as shown below,HA_READ_KEY_EXACTis the SQL layer’s search mode for an exact match, meaning that InnoDB should precisely locate the specifiedsearch_tuple. In InnoDB’s internal system, the corresponding mode isPAGE_CUR_GE, which directs InnoDB to locate the first record in the B+Tree page that is greater than or equal to the specifiedsearch_tuple. The other search modes work similarly, and their names make their purposes clear. - For

index_prev()andindex_next(), InnoDB’s implementation is unified underinnobase::general_fetch()->innobase::row_search_mvcc(). Thus,innobase::row_search_mvcc()needs a direction parameter to distinguish betweenindex_prev()andindex_next():SEL_ROW_PREVandSEL_ROW_NEXT. (Note: Forindex_read(), the direction is 0.)

-

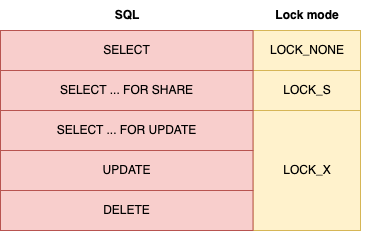

The last parameter is the lock mode. The SQL layer needs to retrieve data through these InnoDB interfaces and simultaneously apply locks. Therefore, it passes the lock mode to

innobase::row_search_mvcc(). This is straightforward, as different SQL statements require different lock modes, as illustrated below. In summary, we now know that

In summary, we now know that innobase::row_search_mvcc()is the key function for reading data and applying locks. It implements theindex_read(),index_prev(), andindex_next()interfaces declared by the SQL layer within InnoDB. It requires the following information: - For

index_read(), it needs the specifiedsearch_entryandsearch_mode. - For

index_prev()andindex_next(), it needs thedirection. - The lock mode is passed down by the SQL layer.

With these background details clear, we can now dive into the implementation of row_search_mvcc().

2. Locking Process in innobase::row_search_mvcc()

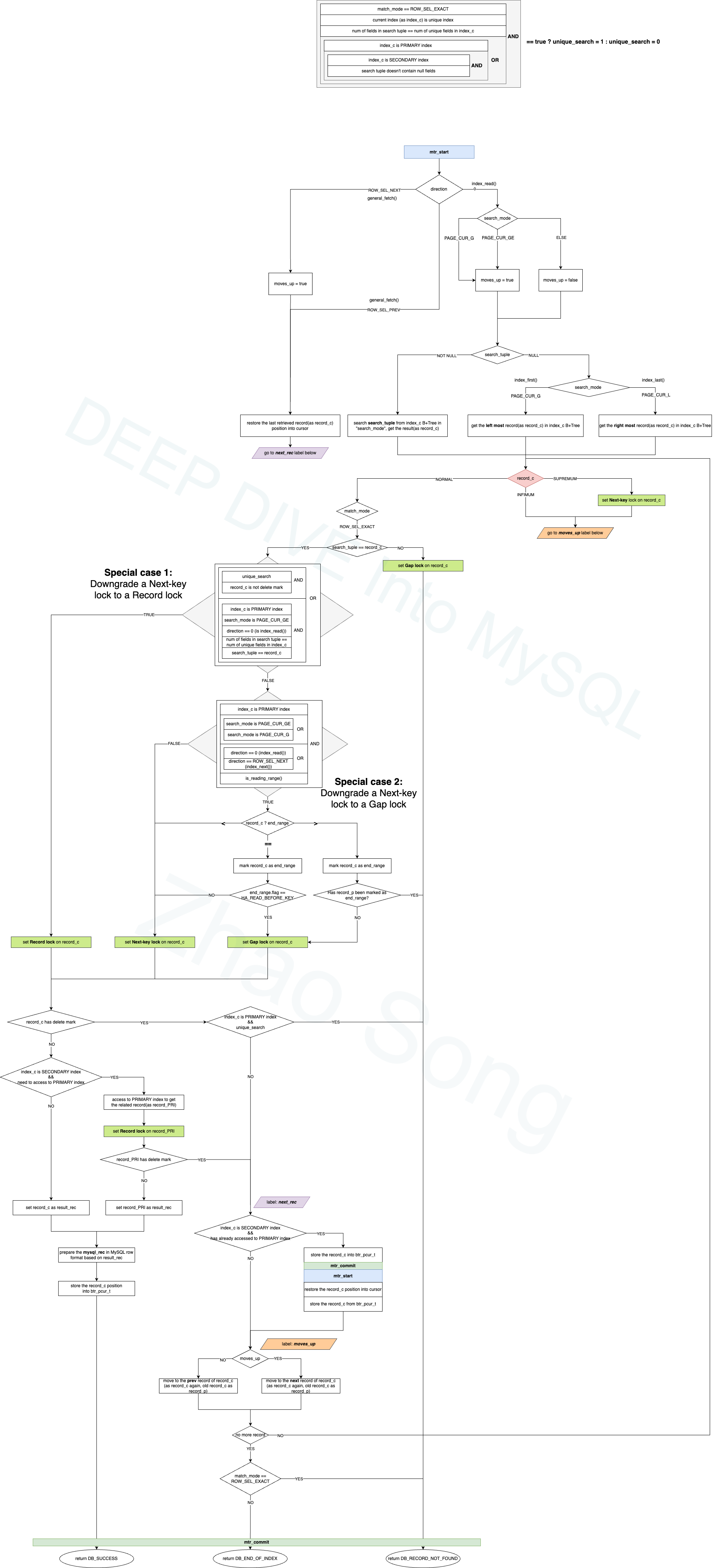

Here is the diagram:

The diagram above shows the entire process of data lookup and transaction locking in row_search_mvcc(), after removing the unrelated parts of the function. It might still seem quite complex (though believe me, it’s much simpler than the actual code). I won’t go through each step in detail here. However, using the background knowledge I’ve introduced earlier, you should be able to follow the process for index_read() and index_prev()/index_next() clearly by referencing the diagram. I will just highlight some key points here:

- The large, standalone box at the top is not part of the overall flow. It represents a condition that checks if it’s a

unique_search, which can be simply understood as an exact lookup usingWHERE =on a unique index. Knowing whether it’s aunique_searchis important because there are certain special treatments in the process (such as downgrading a Nexk-key lock to a record lock or returning early). - The whole process begins with the blue

mtr_start(). As mentioned in the previous post,mtr(mini-transaction) is used by InnoDB for acquiring page latches, locating records, and reading or writing records in the B+Tree. Normally,row_search_mvcc()starts withmtr_start()and ends withmtr_commit(). A special case arises if the currentrow_search_mvcc()operation involves accessing the primary index to read a full record, even though the operation began on a secondary index. To avoid deadlocks on page latches, if the process needs to move to the next record on the secondary index,mtr_commit()must release the latch on the primary index’s page beforehand. (I couldn’t resist explaining why the diagram shows an intermediatemtr_commit(), though it’s not directly related to the transaction lock process and can be ignored.) - This diagram depicts the process under the

repeatable readisolation level, where a Next-key lock is used by default to lock both the current record and the gap before it. However, there are exceptions:- The two large diamond shapes in the diagram represent conditions for downgrading the Next-key lock. Special case 1 checks if it can be downgraded to a regular record lock, while special case 2 checks if it can be downgraded to a gap lock. (Don’t be intimidated by these large boxes; they are just special case judgments for exceptions.)

- If the operation is on a secondary index but requires retrieving the full record from the primary index, the Next-key lock is still applied on the secondary index record, but only a record lock is needed on the corresponding record in the primary index.

- For any retrieved record that has a delete mark, a Next-key lock must still be applied. (Under the

read committedisolation level, after discovering a delete-marked record, the previously applied record lock will be released.) - There are two labels in the diagram: the purple

next_recand the orangemoves_up. These are locations in the flow where execution may need to jump to in certain cases. (Please forgive my use ofgotohere, as the diagram is quite complex.)

This covers the entire process of how SELECT... FOR SHARE/UPDATE, UPDATE, and DELETE acquire transaction locks while searching for data in InnoDB. It’s worth noting that for a plain SELECT, InnoDB doesn’t acquire any transaction locks but instead uses MVCC based on the UNDO log. This significantly reduces lock conflicts between plain SELECT statements and other read/write transactions, thereby improving concurrency. I may dedicate a separate blog post to explain the implementation of MVCC in detail.