The debate over “MySQL vs PostgreSQL, which one is better?” has been around for a long time. As two outstanding representatives of open-source OLTP databases, I personally don’t think one overwhelmingly dominates the other. Transactional database theory has been stable for decades; both systems are practical implementations built under the same theoretical framework.

The differences mainly come from different trade-offs made during engineering practice. I’ve always believed that database development is the art of trade-offs. So I’m planning a series that compares MySQL and PostgreSQL from the perspective of kernel design and implementation, focusing on the different trade-offs they make when pursuing similar goals.

As the first article in this series, I’ll start with the design and implementation differences of the Buffer Pool.

Comparison Dimensions

The Buffer Pool in MySQL and the corresponding module in PostgreSQL (commonly referred to as Shared Buffers) are critical subsystems. Their primary job is to cache on-disk data pages in memory to minimize disk I/O as much as possible, and they are therefore a major factor in relational database performance.

In essence, it is a huge hash table:

- The key corresponds to a specific on-disk data page.

- The value is a pointer (or index) to the in-memory representation of that page.

In the following sections, I compare MySQL and PostgreSQL buffer pool designs from these aspects:

- Hash table structure and implementation

- Eviction policy for old pages and its implementation

- Dirty page flushing strategy and its implementation

1. Hash Table

MySQL

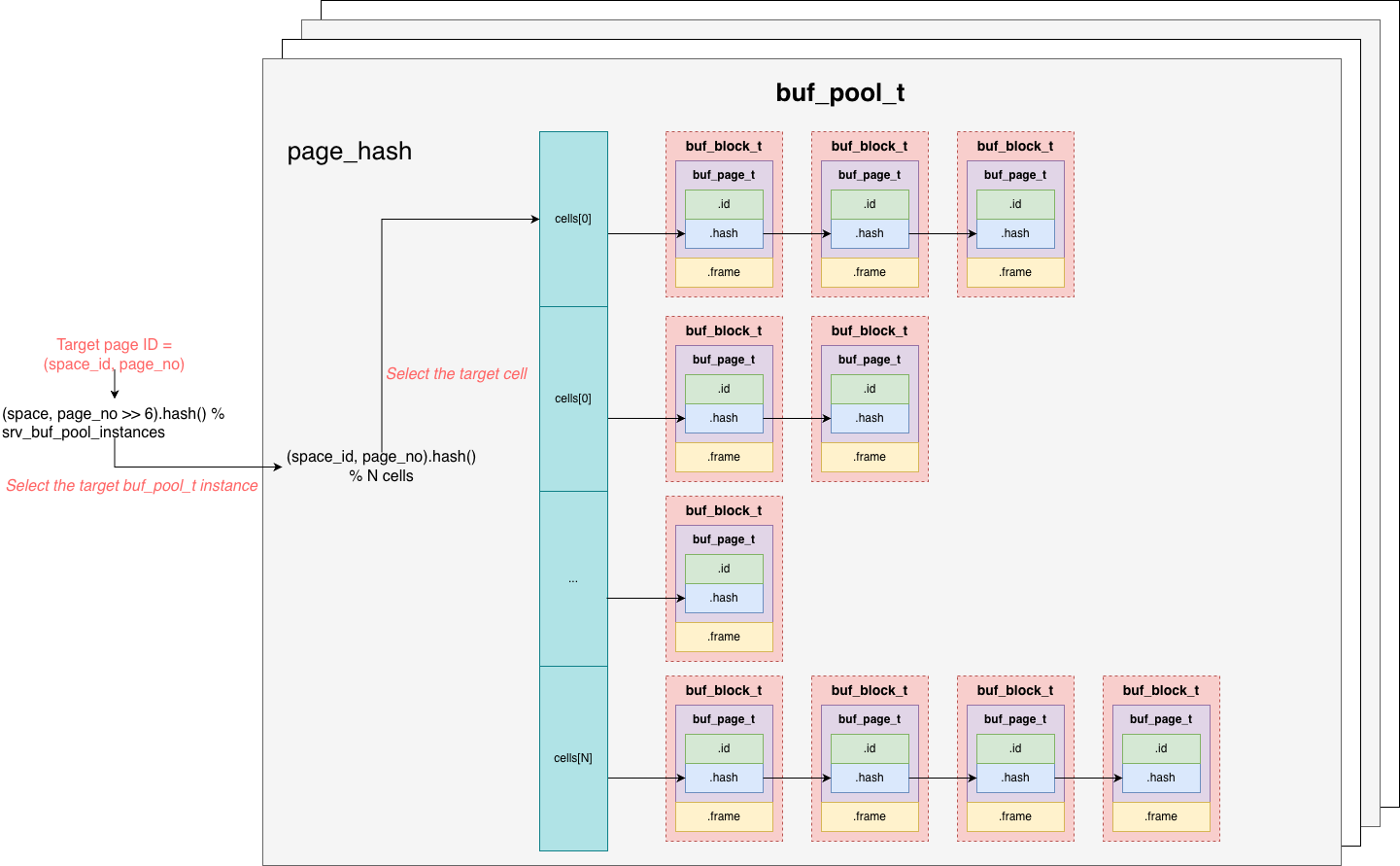

MySQL’s buffer pool is not backed by a single hash table, it uses multiple hash tables. As illustrated conceptually:

-

Multiple

buf_pool_tinstances shard one large buffer pool. Eachbuf_pool_tmaintains its own hash table. -

The hash key is

(space_id, page_no), identifying a specific page within a data file (tablespace). During lookup:- First, it computes a hash using

(space_id, page_no >> 6)to locate the correspondingbuf_pool_tinstance. - Why shift

page_no >> 6? Because MySQL tries to place 64 consecutive pages under the samespace_idinto the samebuf_pool_t. This helps in two ways:- During reads, it enables read-ahead (prefetching contiguous pages).

- During flushing, it increases the chance to flush contiguous dirty pages together, improving I/O utilization.

- After locating the

buf_pool_t, it computes a hash over the full key(space_id, page_no)to find the target cell in that instance’s hash table.- Pages with the same hash value are chained in that cell.

- The lookup then traverses the chain and compares keys to find the target page.

- First, it computes a hash using

-

The hash table stores only pointers to the corresponding page objects (

buf_page_t). The actualbuf_block_tobjects and page frames live in a large memory region.

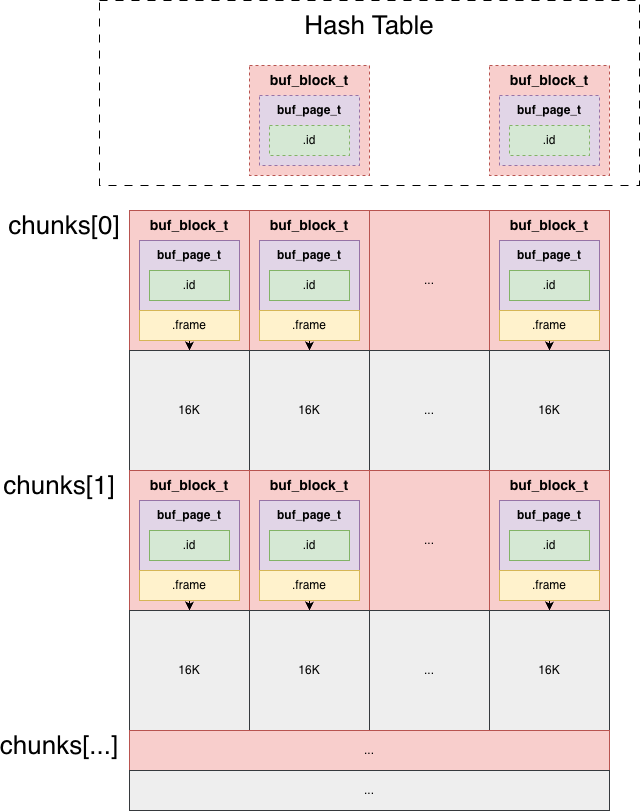

- MySQL splits the page memory into multiple chunks (

buf_chunk_t). - Each chunk is a contiguous block of memory.

- The first part stores per-page metadata (

buf_block_t) for the pages in that chunk. - The second part stores the actual 16KB page frames.

- The mapping between

buf_block_tand the actual page frame is done via theframepointer inbuf_block_t.

- MySQL splits the page memory into multiple chunks (

PostgreSQL

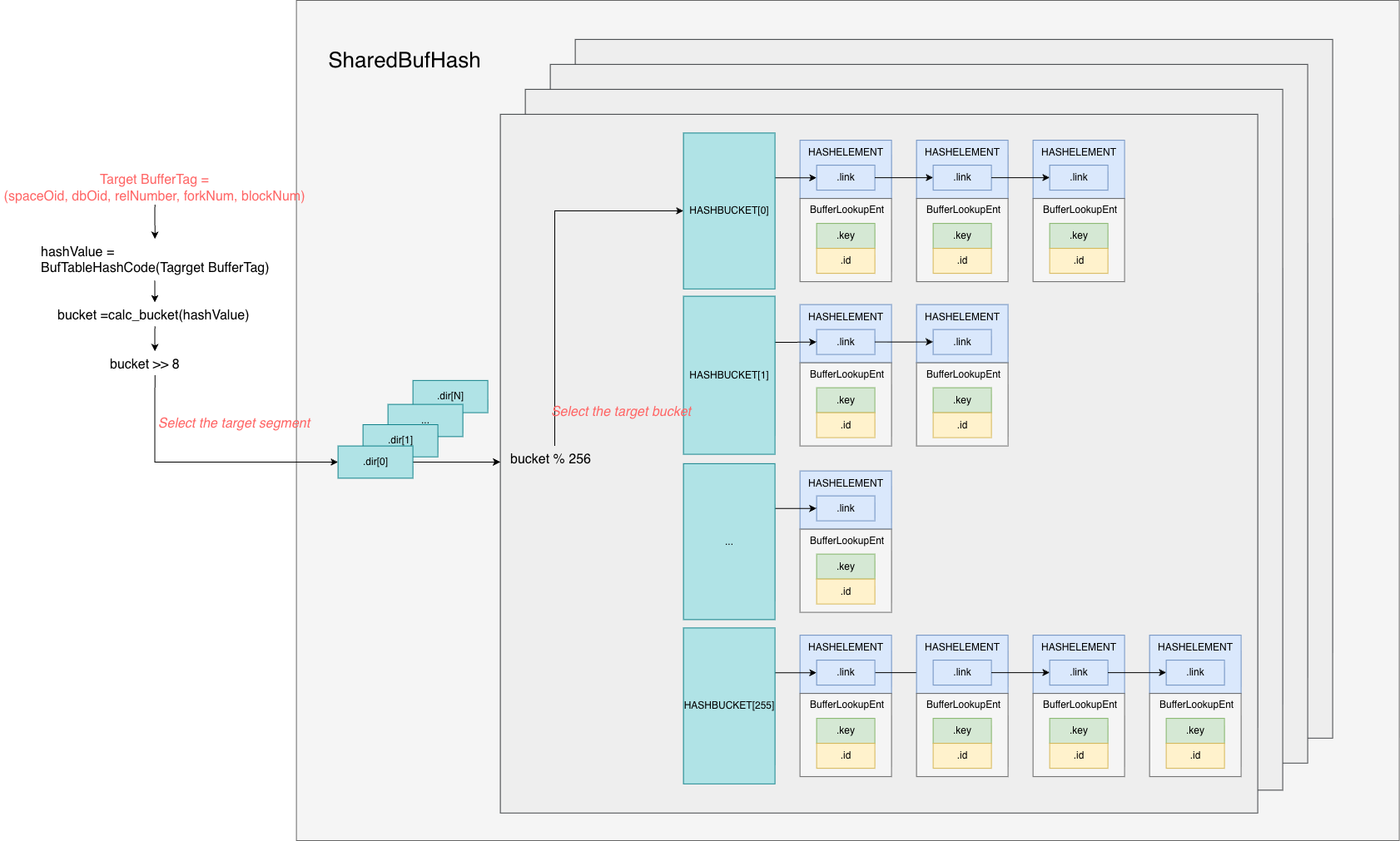

Conceptually (as illustrated):

-

PostgreSQL also shards the shared buffer mapping, with a similar idea.

-

It first hashes the key

(tablespaceOid, dbOid, relNumber, forkNum, blockNum)to obtain a bucket number. -

Then it uses

bucket_number >> 8to locate the directory entry in the first-level mapping, i.e., the segment (dir). -

Each segment contains 256 buckets, so after finding the segment, it uses

bucket_number % 256to locate the bucket within the segment. -

It then traverses the bucket chain, comparing keys one by one to find the page.

-

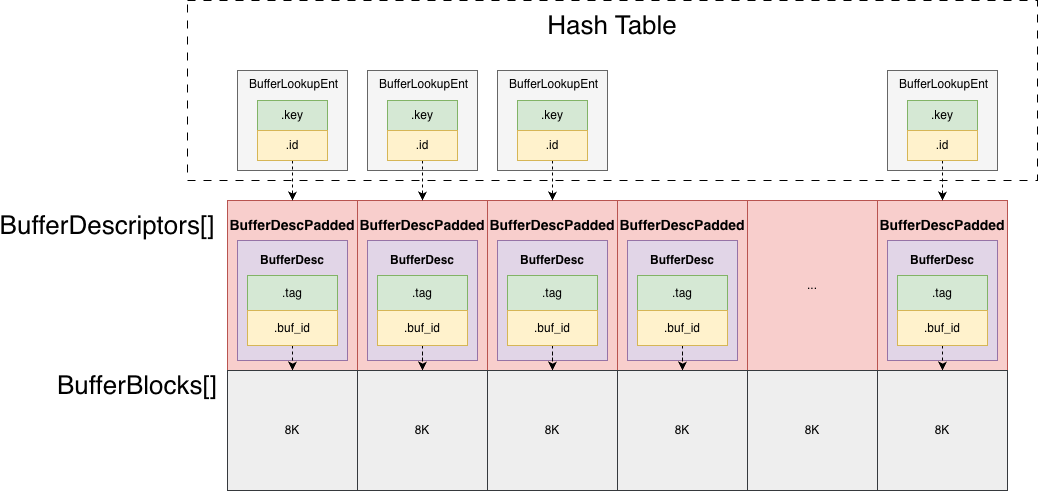

All page frames are stored in one contiguous memory region, as an array:

BufferBlocks[].

- Each page is 8KB.

- PostgreSQL does not split this region into chunks like MySQL does, all pages are stored together.

- Metadata for pages is stored separately in another array:

BufferDescriptors[]. - Both arrays have the same number of elements, equal to the total number of buffers/pages.

- The indices align one-to-one: it is straightforward to locate the actual page frame from the metadata by index.

- The hash table stores

buf_id, which is the index into bothBufferDescriptors[]andBufferBlocks[].

Summary: Both MySQL and PostgreSQL implement fairly standard hash-table-based page lookup; there isn’t a fundamental difference there. The biggest difference is that MySQL splits pages into chunks, which makes it easier to dynamically resize the buffer pool by adding/removing chunks.

2. Eviction Policy for Old Pages (Aging) and Implementation

MySQL

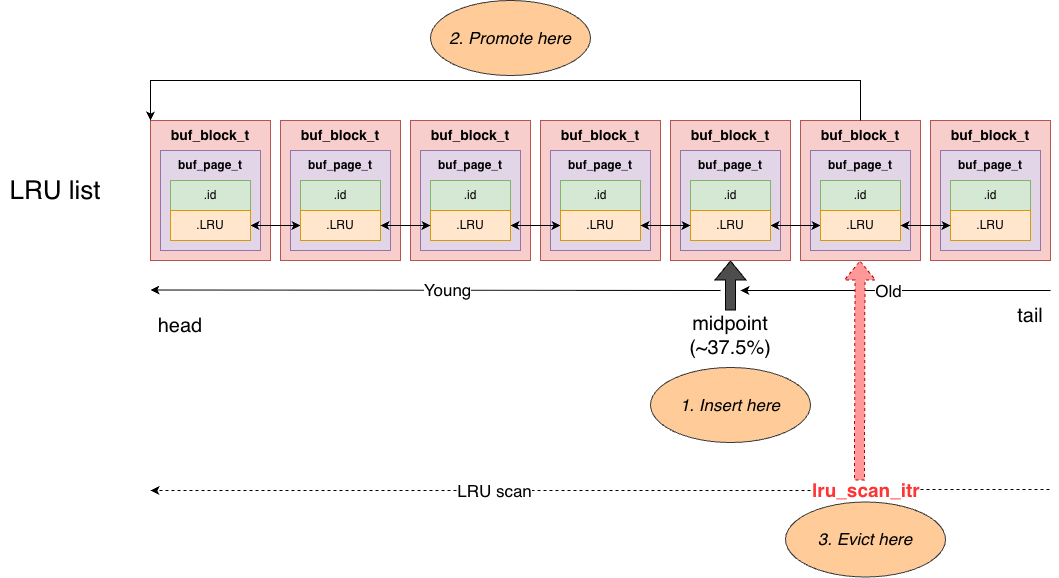

MySQL maintains page aging information in a direct way: pages in the hash table are also linked into an LRU doubly-linked list. Each page’s buf_page_t::LRU is the list node that links the page into the LRU list.

- The LRU head points to the most recently accessed page.

- The LRU tail points to the least recently accessed page.

Each time a page is found via hash lookup, MySQL moves the page to the head of the LRU list via buf_page_t::LRU. Over time, pages that are not accessed drift toward the tail. When memory is insufficient and an old page must be evicted, the tail provides a fast candidate.

Of course, that is the conceptual LRU behavior. MySQL adds an important optimization, because the above design has a major problem: if requests perform table scans, a large number of pages enter the LRU and can overwrite/destroy the existing hot/cold information. To avoid scan workloads disrupting the LRU, MySQL splits the LRU list.

Roughly ~37.5% from the tail, it maintains a midpoint:

- To the left is the young area: the true hot region.

- To the right is the old area: a screening region for newly loaded pages.

All new pages loaded from disk are initially inserted at the midpoint, i.e., the head of the old list. Since it is close to the tail, such pages are more likely to be evicted quickly. If a page is accessed again before it is evicted, MySQL does not immediately promote it to the young region. Instead, it records the first access time, and the page’s position stays unchanged. Only when it is accessed again, and the elapsed time since the first access exceeds innodb_old_blocks_time (default 1 second), will it be promoted to the LRU head (young region). As a result, pages introduced by full table scans typically stay in the old area for less than 1 second and are evicted quickly, without polluting the hot working set in the young region.

When a user thread needs to read a disk page but the buffer pool is full, it evicts an old page from the LRU tail and uses that frame to load the needed page. But eviction is not that trivial. Below is the concrete eviction procedure when a user thread needs a new page:

First attempt (n_iterations == 0)

- First, try the free list. If a free page is found, return it. Otherwise:

- If

try_LRU_scan == true, it indicates a partial LRU scan is allowed. Scan from the tail forward, at most 100 pages.- If an evictable page is found, reset it and move it to the free list, then return to step 1 and retry.

- If no evictable page is found, set

try_LRU_scan = falseto tell other user threads that partial LRU scanning is ineffective, so they should skip partial scans and go directly to the single-page flush path.

- Notify the page cleaner thread that free pages are insufficient and it should accelerate cleaning.

- Scan forward from the tail.

- If a clean evictable page is found, evict it directly.

- Otherwise, locate the first dirty page that can be flushed; perform a synchronous flush of that single page; then add it to the free list and proceed to the next attempt.

Second attempt (n_iterations == 1)

- Same as first attempt step 1.

- Perform a full LRU list scan starting from the tail, searching for an evictable page; if found, move it to the free list and return to step 1 to retry. If that fails:

- Same as first attempt step 3.

- Same as first attempt step 4.

Third and subsequent attempts (n_iterations > 1)

- Same as first attempt step 1.

- Same as second attempt step 2.

- Same as first attempt step 3.

- Sleep for 10ms.

- Same as first attempt step 4.

One more detail worth mentioning: the LRU scan does not always start from the tail for every thread. Each buf_pool_t maintains a global scan cursor lru_scan_itr (type LRUItr). After a thread finishes scanning, it leaves the cursor at its current position, and the next thread continues scanning from there, avoiding multiple threads repeatedly scanning the same region. Only when the cursor is empty/invalid, or still within the old region (meaning the previous scan did not progress far enough), will it be reset back to the tail. In addition, single-page flushing (step 4) uses another independent cursor single_scan_itr; these two cursors do not interfere with each other.

PostgreSQL

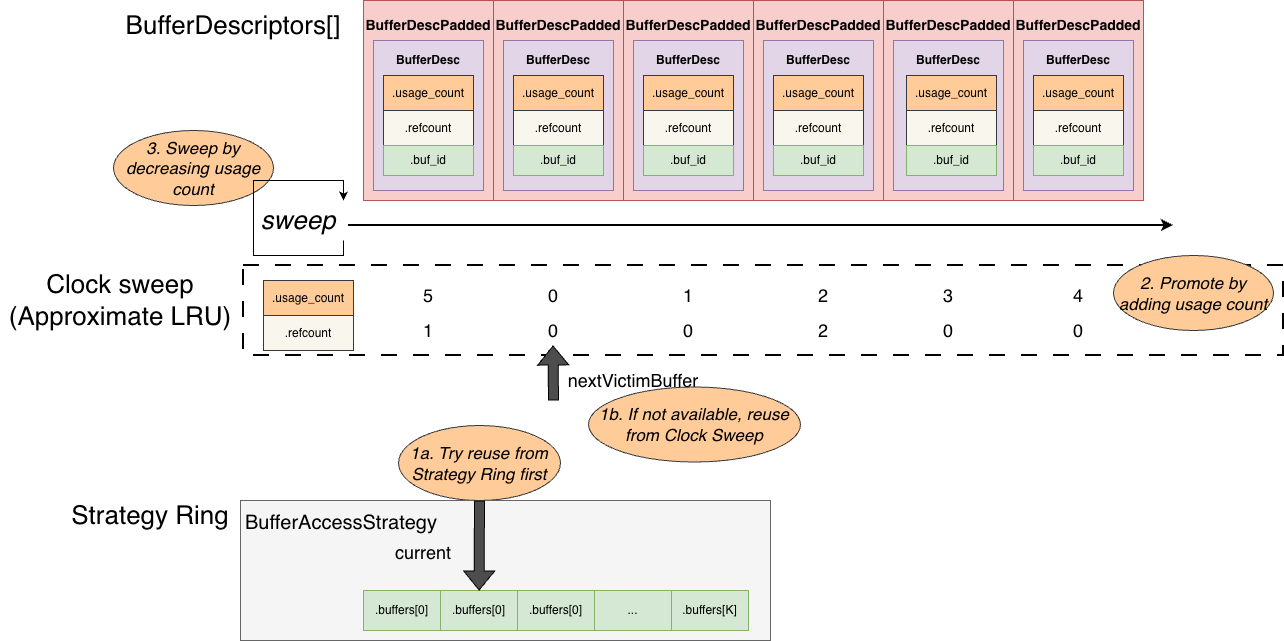

PostgreSQL does not maintain a global LRU list like MySQL does, but that doesn’t mean it does not perform LRU-style eviction. It simply takes another path.

All page metadata lives in the BufferDescriptors[] array. Each BufferDescriptor has two fields representing the current usage state of its corresponding page:

refcount: how many backends are currently using (pinning) the pageusage_count: the accumulated number of accesses to the page (capped at 5, When accessed via a ring buffer strategy, it is only incremented if it is currently 0, limiting it to 1)

Whenever a backend accesses a page via the hash table, it increments both refcount and usage_count. When the backend is done with the page, it only decrements refcount. Therefore, usage_count serves as an approximate LRU weight (but not unbounded, it stops increasing once it reaches 5).

When a backend tries to load a page from disk but finds no free page, it starts a clock sweep: it traverses BufferDescriptors circularly. If a buffer is not currently used by any backend (refcount == 0), it decrements usage_count (cooling down the LRU weight) and continues sweeping. Eventually it finds a buffer where both refcount == 0 and usage_count == 0, and that buffer becomes the victim for eviction.

Of course, this alone is still insufficient to prevent LRU pollution from one-time full scans. PostgreSQL has its own optimization: introducing a local ring buffer.

Each backend has its own local ring buffer: essentially a fixed-length array of buffer IDs. A buffer ID points to a page slot in the global BufferDescriptors. The ring buffer limits how many global buffers the backend consumes at once, so eviction is more likely to happen within the ring buffer itself, reducing pollution of the global shared buffers.

More concretely, suppose a backend is performing a sequential scan and the upper layer marks the operation to use the ring buffer. When reading pages via the hash table:

- If the backend’s local ring buffer is not full, it stores the buffer ID into the ring buffer.

- As reading continues, the ring buffer becomes full.

- After it is full, when it needs to read the next page:

- It checks the page at the ring buffer’s current cursor position.

- If that buffer is not used by other backends (

refcount == 0andusage_count <= 1), it reuses it directly: evict and load the next page into it. - If that buffer is currently used by other backends, it falls back to searching in

BufferDescriptorsfor another available buffer to load the next page, and then replaces the current ring entry with the new buffer ID.

Here you can see the different approaches MySQL and PostgreSQL take for the same scenario. MySQL introduces an “old/young” split in the global LRU list as a general strategy to prevent pollution. PostgreSQL’s ring buffer is essentially also an “old area”, but it relies on higher-level operation tagging: only scan-heavy operations such as VACUUM, sequential scan, bulk insert, etc., will use the ring buffer.

Below is the complete procedure PostgreSQL uses to find a free buffer when a backend needs one:

-

Determine whether to use the ring buffer. If yes, inspect the buffer at the ring’s current cursor position:

a. If it has not been used before, the ring is not full yet, go to step 2.

b. Otherwise the ring is full. If the buffer is not used by any backend (

refcount == 0andusage_count <= 1), it can be reused immediately, return this buffer.c. If the buffer is used by other backends, fall back to step 2 to find a buffer from the global pool; after success, replace the current ring entry with the newly found buffer ID.

-

Check the free list. If a buffer is available, return it.

-

Start clock sweep: traverse from

nextVictimBuffer(the current sweep cursor inBufferDescriptors):- If

refcount != 0, skip. - Otherwise, if

usage_count != 0, decrement it (cooling down) and continue. - Otherwise, the buffer is evictable. If it is not dirty, return it immediately. If it is dirty, flush it and then return it.

- Advance

nextVictimBufferaccordingly.

- If

Summary: MySQL and PostgreSQL are similar in essence: both are LRU-like. MySQL chooses to implement an explicit LRU list for more precise eviction, at the cost of additional overhead to maintain the list. PostgreSQL uses reference counting plus usage_count as an approximate LRU, avoiding the locking overhead of maintaining a true LRU list but losing precision. This is the result of different trade-offs. Another notable difference: when a MySQL foreground thread tries to find a free page, it tends to prefer evicting old pages that are not dirty first; PostgreSQL’s sweep does not have an explicit priority between dirty and clean pages in the same sense.

3. Dirty Page Flushing Strategy and Implementation

Earlier we mentioned that MySQL user threads and PostgreSQL backends may flush a single dirty page when searching for a free page (single-page flush). However, such foreground single-page flushing is only an emergency measure when no free page is available.

For normal bulk flushing, both MySQL and PostgreSQL have dedicated background threads/processes. The goal is to flush dirty pages in advance and evict old pages so that foreground threads can quickly find free pages.

Background flushing has two goals:

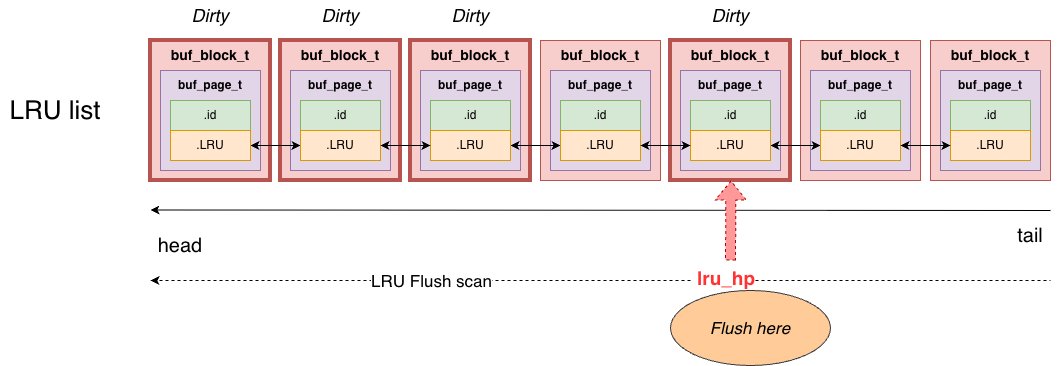

- LRU flush: flush old pages in advance based on foreground free-page pressure, reducing foreground wait time for free pages.

- Checkpoint flush: flush dirty pages associated with the oldest WAL LSN to advance the checkpoint, purge old WAL, and reduce crash recovery time.

MySQL

In MySQL (InnoDB), background flushing is performed by page cleaner threads, consisting of one coordinator and N workers.

Coordinator

- Sleep for ~1 second, or be woken by a foreground thread.

- Check whether work is needed (sync flush / adaptive / idle). If yes:

- Dynamically calculate the number of dirty pages to flush in the next batch:

n_pages. - Pass

n_pagesto all workers and wake them up. Each worker is responsible for onebuf_pool_tslot. The coordinator itself also works as worker 0. - Wait for all workers to finish.

Worker

- Wait to be woken by the coordinator.

- Locate the assigned

buf_pool_tslot. - LRU flush: scan from the LRU tail forward, scanning at most

srv_LRU_scan_depthpages.- If a page is clean and not being used, move it directly from the LRU list to the free list.

- If a page can be flushed, initiate asynchronous I/O; after I/O completes, move it into the free list.

- Stop early if the free list length reaches

srv_LRU_scan_depth.

- Checkpoint flush: scan from the flush list tail forward and flush continuously until:

- the number of flushed pages satisfies the quota assigned by the coordinator, or

- the WAL LSN advances to the target LSN assigned by the coordinator.

- Finish and report to the coordinator.

Now, step 3 in the coordinator is adaptive: it calculates the flush workload and the target LSN advancement. The logic is as follows:

a. Based on dirty page percentage (get_pct_for_dirty())

Compute dirty_pct, the percentage of dirty pages in the buffer pool:

- If

innodb_max_dirty_pages_pct_lwm(low watermark) is set anddirty_pct >= lwm, start progressive flushing and return the percentage ofio_capacityas:dirty_pct * 100 / (max_dirty_pages_pct + 1) - If no low watermark is set, but

dirty_pct >= innodb_max_dirty_pages_pct(high watermark), flush at 100%io_capacity. - Otherwise, do not flush based on dirty ratio (return 0).

b. Based on redo log age (get_pct_for_lsn(age))

Compute checkpoint age:

age = current_lsn - oldest_lsn

- If

age < innodb_adaptive_flushing_lwm(default 10% of redo log capacity), no adaptive flushing needed (return 0). - If

ageexceeds the low watermark:age_factor = age * 100 / limit_for_dirty_page_ageReturn the percentage ofio_capacityas:(max_io_capacity / io_capacity) * age_factor * sqrt(age_factor) / 7.5

This is a super-linear growth curve: as redo space approaches exhaustion, flushing ramps up aggressively.

Combined calculation (set_flush_target_by_lsn())

Take:

pct_total = max(pct_for_dirty, pct_for_lsn)

Then compute the target LSN:

target_lsn = oldest_lsn + lsn_avg_rate * 3

(i.e., advance by 3× the recent average redo generation rate; buf_flush_lsn_scan_factor = 3)

Then traverse each buffer pool instance’s flush list and count the number of pages whose oldest_modification <= target_lsn. Call this number pages_for_lsn (pages that must be flushed to advance checkpoint to target_lsn).

Finally, take the average of three estimates:

n_pages = (PCT_IO(pct_total) + page_avg_rate + pages_for_lsn) / 3

Where:

PCT_IO(pct_total)is the I/O demand estimated from dirty ratio / redo age.page_avg_rateis the recent actual average flushing rate (moving average across multiple iterations).pages_for_lsnis the precise demand obtained from scanning the flush list.

Averaging these three makes the flushing rate smoother and avoids abrupt oscillation. n_pages is capped by srv_max_io_capacity.

If redo pressure is high (pct_for_lsn > 30), the per-instance flush quota is weighted by how many pages in each instance’s flush list need flushing; otherwise, it is evenly distributed across instances.

Sync Flush mode

When redo log space is extremely tight (checkpoint cannot keep up with redo generation), log_sync_flush_lsn() returns non-zero and the coordinator enters sync flush mode:

- It no longer sleeps for 1 second; it starts the next iteration immediately.

n_pagesis set directly topages_for_lsn(no averaging), with a lower bound ofsrv_io_capacity.- It loops until redo pressure is relieved.

Idle flushing

When the server is idle (no user activity) and the 1-second sleep times out, the coordinator does not run the adaptive algorithm. Instead, it flushes in the background using innodb_idle_flush_pct percent of innodb_io_capacity (default 100%), keeping the buffer pool clean.

PostgreSQL

PostgreSQL also has both LRU flush and checkpoint flush, but unlike MySQL’s unified page cleaner, PostgreSQL separates responsibilities:

bgwriterhandles LRU flushcheckpointerhandles checkpoint flush

1. bgwriter

The goal of bgwriter is to predict the upcoming demand for free buffers based on historical and current pressure, and try to free enough buffers before backends are forced into heavy clock sweep work (i.e., flush dirty pages that are otherwise reusable victims).

The overall flow:

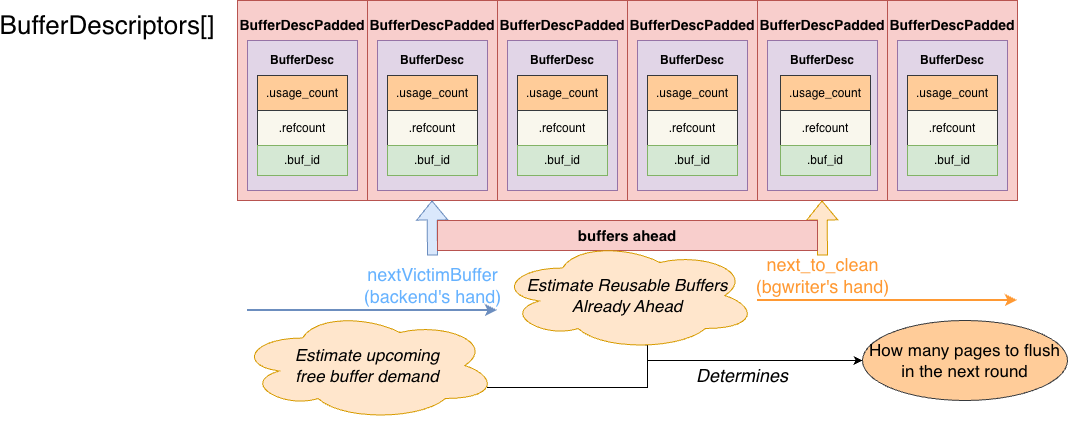

-

Collect historical info from clock sweep, including:

strategy_buf_id: the current backend clock sweep positionstrategy_passes: how many full sweeps have been completedrecent_alloc: how many buffers have been allocated by backends since the last bgwriter recycle

-

Compare

bgwriter’s current positionnext_to_cleanwith clock sweep’sstrategy_buf_id, and determine how far ahead it is:bufs_to_lap: number of buffers bgwriter must scan fornext_to_cleanto “lap” (catch up to)strategy_buf_id.- Case 1: same pass, bgwriter ahead →

bufs_to_lapis the remaining distance to lap. - Case 2: same pass, bgwriter behind → set

next_to_cleantostrategy_buf_id, setbufs_to_lap = NBuffers, effectively reset bgwriter. - Case 3: bgwriter already one full pass ahead →

bufs_to_lapmay be negative, meaning bgwriter has scanned everything it can scan; no need to scan in this round.

- Case 1: same pass, bgwriter ahead →

bufs_ahead = NBuffers - bufs_to_lap(how many buffers bgwriter is ahead of sweep)

-

Based on the history above, compute how many buffers clock sweep needs to scan to find one free buffer, i.e.

scans_per_alloc. Maintain an exponential moving average:smoothed_density += (scans_per_alloc - smoothed_density) / 16; -

Maintain

smoothed_allocsimilarly:- If

smoothed_alloc < recent_alloc, setsmoothed_alloc = recent_alloc(fast attack). - Otherwise decay slowly using EMA:

smoothed_alloc += (recent_alloc - smoothed_alloc) / 16;(slow decay)

- If

-

Compute the prediction for the next round:

upcoming_alloc_est = smoothed_alloc * bgwriter_lru_multiplier(predict upcoming allocations)- Estimate how many reusable buffers exist in the region bgwriter is ahead:

reusable_buffers_est = bufs_ahead / smoothed_density - Ensure minimum progress:

min_scan_buffers = NBuffers / (120s / 200ms)Then:upcoming_alloc_est = max(upcoming_alloc_est, min_scan_buffers + reusable_buffers_est)

This “minimum progress” ensures that even if the system is idle, bgwriter will scan the entire buffer pool in about 120 seconds, continuously cleaning dirty pages.

-

Scan from

next_to_clean. For each buffer, bgwriter only considers buffers withrefcount == 0andusage_count == 0(truly reusable candidates). It skips buffers in use or recently used. If a candidate is dirty, it flushes it synchronously. Stop scanning when any of these is met:bufs_to_lapreaches 0 (caught up to clock sweep)reusable_buffersreachesupcoming_alloc_est(freed enough reusable buffers)num_writtenreachesbgwriter_lru_maxpages(default 100) to avoid excessive I/O in one round

After one scan round, bgwriter sleeps for bgwriter_delay (default 200ms) before next iteration. If bufs_to_lap == 0 and recent_alloc == 0 (no allocation activity), bgwriter enters hibernation and sleeps longer, until a backend needing buffers wakes it via latch.

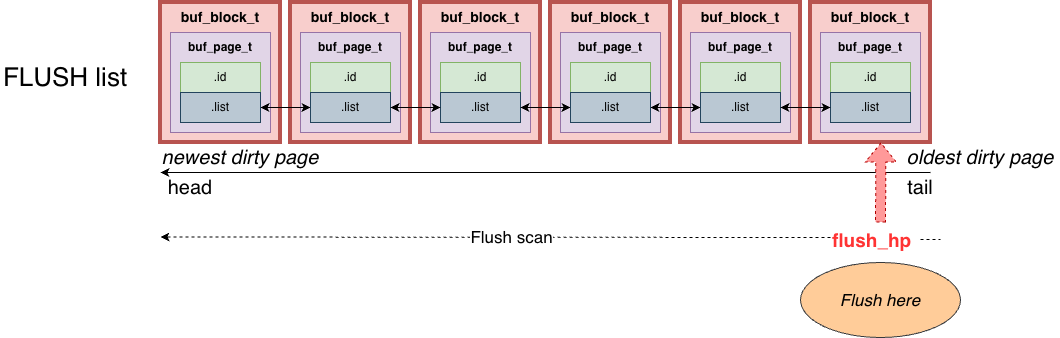

2. checkpointer

The goal of checkpointer is to flush all dirty pages up to a consistency point, forming a checkpoint. This advances WAL recycling and reduces how much WAL must be replayed during crash recovery. Unlike bgwriter, checkpointer does not care whether a page was recently used, it must flush all pages that were dirty at checkpoint start.

Trigger conditions: in the main loop, checkpointer triggers a checkpoint when any of the following occurs:

- Time since last checkpoint exceeds

checkpoint_timeout(default 5 minutes) - WAL volume exceeds

max_wal_sizeand backends notify checkpointer - User manually runs

CHECKPOINT - Shutdown checkpoint during server shutdown

Detailed procedure:

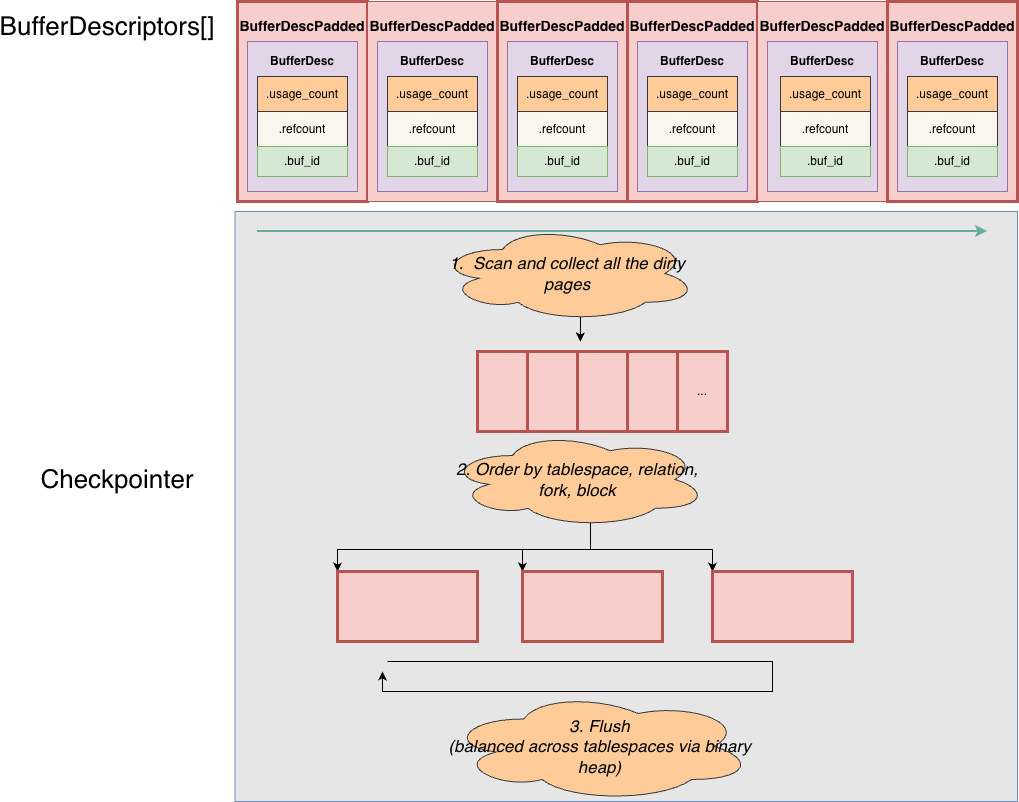

-

Scan and collect dirty buffers: traverse all

NBuffersBufferDescriptors. For each dirty page, set theBM_CHECKPOINT_NEEDEDflag, and collect its identity info intoCkptBufferIds[](tablespace OID, relation number, fork number, block number, etc.). Note: only pages that are already dirty at checkpoint start are included. Pages that become dirty during the checkpoint are not included and will be handled in the next checkpoint. -

Sort: sort

CkptBufferIds[]by(tablespace, relation, fork, block). This clusters pages from the same file and orders them by increasing block number, converting random I/O into more sequential patterns as much as possible. -

Build tablespace-level progress tracking: traverse the sorted array and group by tablespace. For each tablespace, build a

CkptTsStatusstructure tracking total pages to flush and current progress. Put all tablespaces into a binary heap (min-heap), ordered by flush progress. -

Balanced flushing across tablespaces: repeatedly pop the tablespace with the lowest progress from the heap, flush its next dirty page (via

SyncOneBuffer), update its progress, then re-heapify. The purpose is to spread writes evenly across tablespaces (possibly on different disks), instead of flushing one tablespace completely before another. Unlike bgwriter, checkpointer callsSyncOneBufferwithskip_recently_used = false, meaning it will flush buffers withBM_CHECKPOINT_NEEDEDregardless of recent usage. -

Write throttling: after flushing each page, call

CheckpointWriteDelay()to throttle. The goal is to finish flushing within:checkpoint_completion_target(default 0.9) ×checkpoint_timeout. The logic compares:- flush progress (flushed pages / total),

- elapsed time progress,

- WAL progress.

- If flush progress is ahead of both time progress and WAL progress (

IsCheckpointOnSchedule == true), sleep 100ms. - If lagging behind, do not sleep and flush at full speed.

- In IMMEDIATE mode (e.g., shutdown checkpoint) or under urgent checkpoint requests, do not throttle.

This spreads checkpoint I/O across the entire checkpoint window and avoids I/O spikes.

-

Writeback coalescing: if not using

O_DIRECT, similar to bgwriter, useWritebackContextto collect tags for flushed pages. After accumulating enough, batch-callIssuePendingWritebacks(), sort and coalesce adjacent blocks, and useposix_fadviseto hint the kernel to write back OS cache pages to disk. After checkpoint completion, force one moreIssuePendingWritebacks()to ensure all pending writebacks are issued.

Summary: Although the implementations differ significantly, both MySQL and PostgreSQL aim to pre-clean pages in the background so that foreground threads can quickly find free pages. PostgreSQL’s bgwriter predicts upcoming buffer allocation demand from foreground activity; MySQL’s page cleaner reacts to dirty page pressure and redo log age.

From an engineering perspective, their differences largely come down to the trade-off between linked lists and arrays:

- With linked lists, MySQL can precisely obtain LRU ordering and dirty-page ordering from old to new. This greatly improves precision in eviction and flushing decisions. In particular, for checkpoint flushing, it can directly take the oldest dirty pages from the flush list tail to advance checkpoint quickly. The trade-off is the cost of maintaining those lists.

- PostgreSQL sacrifices some precision and scans arrays instead, avoiding the additional overhead of maintaining linked lists. It is also worth noting that PostgreSQL’s checkpoint flushing emphasizes balanced progress across tablespaces rather than globally prioritizing the oldest dirty pages to advance checkpoint in small steps.