SIMD (Single instruction, multiple data) is often one of the key optimization techniques in vector search. In particular, when computing the distance between two vectors, SIMD can transform what was originally a one-dimensional-at-a-time calculation into 8- or 16-dimensions-at-a-time, significantly improving performance.

Here, as I mentioned in previous posts, MariaDB and pgvector take different approaches:

- MariaDB: directly implements distance functions using SIMD instructions.

- pgvector: implements distance functions in a naive way and relies on compiler optimization (

-ftree-vectorize) for vectorization.

To better understand the benefits of SIMD vectorization, and to compare these two approaches, I ran a series of benchmarks — and discovered some surprising performance results along the way.

1. Test Environment and Method

Environment

- AWS EC2: c5.4xlarge, 16 vCPUs, 32 GiB memory

- Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8124M CPU @ 3.00GHz

- gcc (Ubuntu 13.3.0-6ubuntu2~24.04) 13.3.0

Method

-

First, I implemented 4 different squared L2 distance (L2sq) functions (i.e., Euclidean distance without the square root):

- Naive L2sq implementation

static inline double l2sq_naive_f32(const float* a, const float* b, size_t n) { float acc = 0.f; for (size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) { float d = a[i] - b[i]; acc += d * d; } return (double)acc; }- Naive high-precision L2sq (converting float to double before computation)

static inline double l2sq_naive_f64(const float* a, const float* b, size_t n) { double acc = 0.0; for (size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) { double d = (double)a[i] - (double)b[i]; acc += d * d; } return acc; }- SIMD (AVX2) L2sq implementation, computing 8 dimensions at a time

// Reference: simSIMD SIMSIMD_PUBLIC void simsimd_l2sq_f32_haswell(simsimd_f32_t const *a, simsimd_f32_t const *b, simsimd_size_t n, simsimd_distance_t *result) { __m256 d2_vec = _mm256_setzero_ps(); simsimd_size_t i = 0; for (; i + 8 <= n; i += 8) { __m256 a_vec = _mm256_loadu_ps(a + i); __m256 b_vec = _mm256_loadu_ps(b + i); __m256 d_vec = _mm256_sub_ps(a_vec, b_vec); d2_vec = _mm256_fmadd_ps(d_vec, d_vec, d2_vec); } simsimd_f64_t d2 = _simsimd_reduce_f32x8_haswell(d2_vec); for (; i < n; ++i) { float d = a[i] - b[i]; d2 += d * d; } *result = d2; } SIMSIMD_INTERNAL simsimd_f64_t _simsimd_reduce_f32x8_haswell(__m256 vec) { // Convert the lower and higher 128-bit lanes of the input vector to double precision __m128 low_f32 = _mm256_castps256_ps128(vec); __m128 high_f32 = _mm256_extractf128_ps(vec, 1); // Convert single-precision (float) vectors to double-precision (double) vectors __m256d low_f64 = _mm256_cvtps_pd(low_f32); __m256d high_f64 = _mm256_cvtps_pd(high_f32); // Perform the addition in double-precision __m256d sum = _mm256_add_pd(low_f64, high_f64); return _simsimd_reduce_f64x4_haswell(sum); } SIMSIMD_INTERNAL simsimd_f64_t _simsimd_reduce_f64x4_haswell(__m256d vec) { // Reduce the double-precision vector to a scalar // Horizontal add the first and second double-precision values, and third and fourth __m128d vec_low = _mm256_castpd256_pd128(vec); __m128d vec_high = _mm256_extractf128_pd(vec, 1); __m128d vec128 = _mm_add_pd(vec_low, vec_high); // Horizontal add again to accumulate all four values into one vec128 = _mm_hadd_pd(vec128, vec128); // Convert the final sum to a scalar double-precision value and return return _mm_cvtsd_f64(vec128); }- SIMD (AVX-512) L2sq implementation, computing 16 dimensions at a time

// Reference: simSIMD SIMSIMD_PUBLIC void simsimd_l2sq_f32_skylake(simsimd_f32_t const *a, simsimd_f32_t const *b, simsimd_size_t n, simsimd_distance_t *result) { __m512 d2_vec = _mm512_setzero(); __m512 a_vec, b_vec; simsimd_l2sq_f32_skylake_cycle: if (n < 16) { __mmask16 mask = (__mmask16)_bzhi_u32(0xFFFFFFFF, n); a_vec = _mm512_maskz_loadu_ps(mask, a); b_vec = _mm512_maskz_loadu_ps(mask, b); n = 0; } else { a_vec = _mm512_loadu_ps(a); b_vec = _mm512_loadu_ps(b); a += 16, b += 16, n -= 16; } __m512 d_vec = _mm512_sub_ps(a_vec, b_vec); d2_vec = _mm512_fmadd_ps(d_vec, d_vec, d2_vec); if (n) goto simsimd_l2sq_f32_skylake_cycle; *result = _simsimd_reduce_f32x16_skylake(d2_vec); } ...... -

I generated a dataset of 10,000 float vectors (dimension = 1024, 64B aligned) and one target vector. Then, for the following 5 scenarios, I searched for the vector with the closest L2sq distance to the target. Each distance computation was repeated 16 times (to create a CPU-intensive workload), and each scenario was executed 5 times, taking the median runtime to eliminate random fluctuations:

- SIMD L2sq implementation

- Naive L2sq implementation

- Naive L2sq with compiler vectorization disabled (

-fno-tree-vectorize -fno-builtin -fno-lto -Wno-cpp -Wno-pragmas) - Naive high-precision L2sq implementation

- Naive high-precision L2sq with compiler vectorization disabled

-

Compile with AVX2 (

-O3 -mavx2 -mfma -mf16c -mbmi2) and run the 5 scenarios. -

Compile with AVX-512 (

-O3 -mavx512f -mavx512dq -mavx512bw -mavx512vl -mavx512cd -mfma -mf16c -mbmi2) and run the 5 scenarios again.

2. Results and Analysis

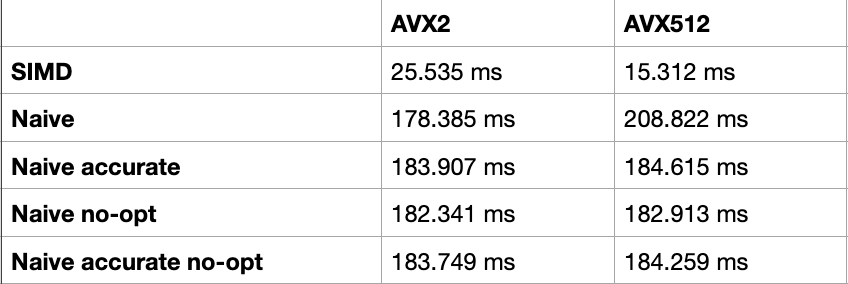

Expected results:

-

SIMD L2sq implementations are much faster than others, and AVX-512 outperforms AVX2 since it processes 16 dimensions at once instead of 8.

-

Under AVX2, naive L2sq (178.385ms) is faster than naive high-precision L2sq (183.973ms), because the latter incurs float→double conversion overhead.

-

Under both AVX2 and AVX-512, naive implementations with compiler vectorization disabled perform the worst, since they are forced into scalar execution.

Unexpected Results

In addition to the expected results above, some surprising findings appeared:

- For naive L2sq, AVX-512 performance (208.822ms) was actually slower than AVX2 (178.385ms).

- With AVX-512, naive L2sq was slower than naive high-precision L2sq.

Both deserve deeper analysis.

(1) Why was naive L2sq with AVX-512 slower than with AVX2?

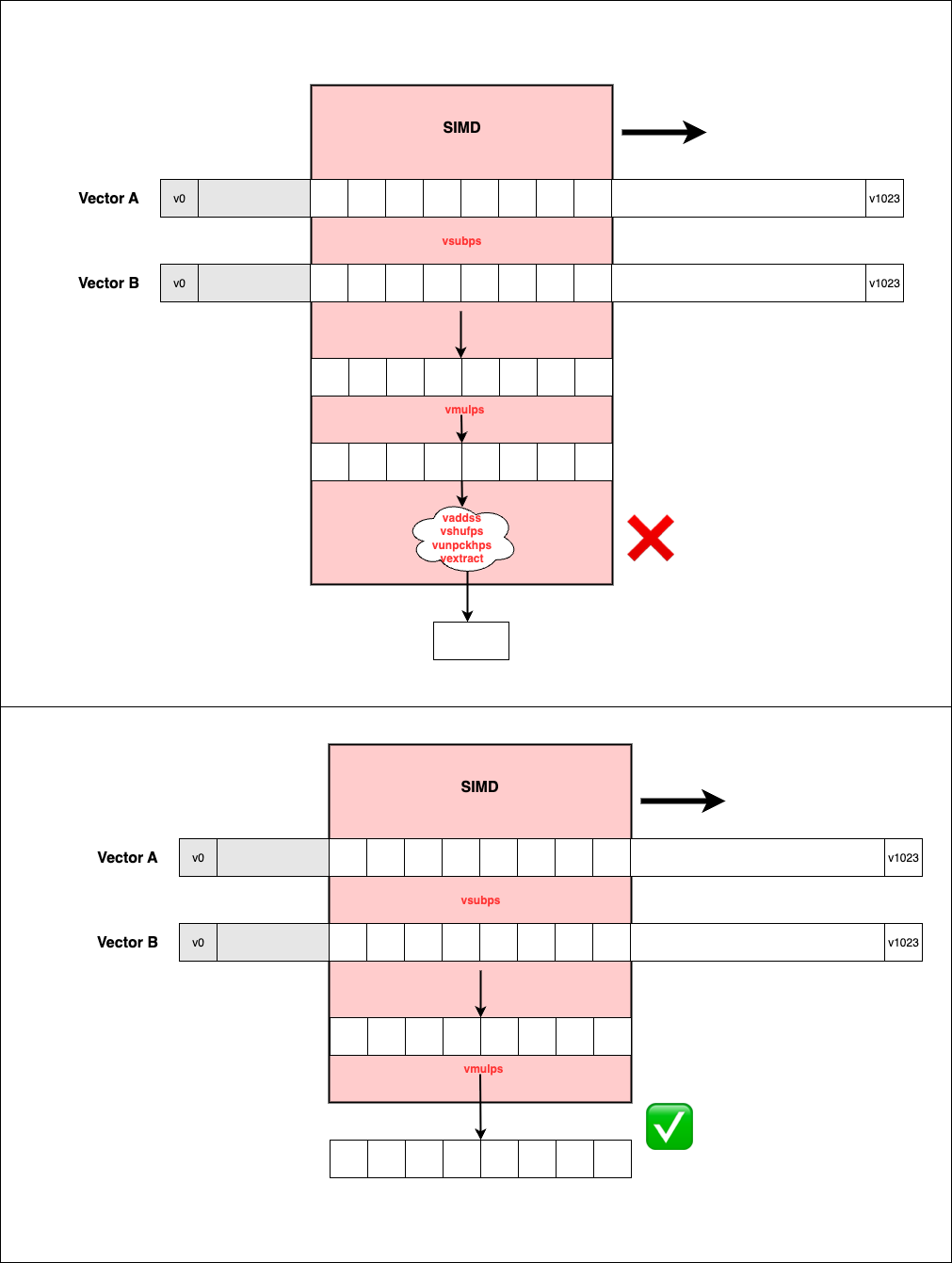

Although this was a naive implementation, with -O3 we would expect the compiler to auto-vectorize. However, the vectorized result generated by the compiler was far worse than our manual SIMD implementation, and AVX-512 even performed worse than AVX2.

To investigate further, I used objdump to examine the AVX2 and AVX-512 binaries for l2sq_naive_f32().

-

Under AVX2:

0000000000007090 <_ZL19l2sq_naive_f32PKfS0_m>: ... ... 70b7: 48 c1 ee 03 shr rsi,0x3 70bb: 48 c1 e6 05 shl rsi,0x5 70bf: 90 nop 70c0: c5 fc 10 24 07 vmovups ymm4,YMMWORD PTR [rdi+rax*1] 70c5: c5 dc 5c 0c 01 vsubps ymm1,ymm4,YMMWORD PTR [rcx+rax*1] 70ca: 48 83 c0 20 add rax,0x20 70ce: c5 f4 59 c9 vmulps ymm1,ymm1,ymm1 70d2: c5 fa 58 c1 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm1 70d6: c5 f0 c6 d9 55 vshufps xmm3,xmm1,xmm1,0x55 70db: c5 f0 c6 d1 ff vshufps xmm2,xmm1,xmm1,0xff 70e0: c5 fa 58 c3 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm3 70e4: c5 f0 15 d9 vunpckhps xmm3,xmm1,xmm1 70e8: c4 e3 7d 19 c9 01 vextractf128 xmm1,ymm1,0x1 70ee: c5 fa 58 c3 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm3 70f2: c5 fa 58 c2 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm2 70f6: c5 f0 c6 d1 55 vshufps xmm2,xmm1,xmm1,0x55 70fb: c5 fa 58 c1 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm1 70ff: c5 fa 58 c2 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm2 7103: c5 f0 15 d1 vunpckhps xmm2,xmm1,xmm1 7107: c5 f0 c6 c9 ff vshufps xmm1,xmm1,xmm1,0xff 710c: c5 fa 58 c2 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm2 7110: c5 fa 58 c1 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm1 ... ...The compiler did use vector instructions (

vmovups,vsubps,vmulps) to compute L2sq in groups of 8 floats. But when folding the 8 results horizontally intoxmm0, it extracted elements usingvshufps,vunpckhps,vextractf128, etc., and then added them one by one with scalarvaddss. Worse, this folding happened in every iteration.

This per-iteration horizontal reduction became the bottleneck. Instead, like the manual SIMD implementation, it should have accumulated vector results across the whole loop and performed just one horizontal reduction at the end.

-

Under AVX-512:

a057: 48 c1 ee 04 shr rsi,0x4 a05b: 48 c1 e6 06 shl rsi,0x6 a05f: 90 nop a060: 62 f1 7c 48 10 2c 07 vmovups zmm5,ZMMWORD PTR [rdi+rax*1] a067: 62 f1 54 48 5c 0c 01 vsubps zmm1,zmm5,ZMMWORD PTR [rcx+rax*1] a06e: 48 83 c0 40 add rax,0x40 a072: 62 f1 74 48 59 c9 vmulps zmm1,zmm1,zmm1 a078: c5 f0 c6 e1 55 vshufps xmm4,xmm1,xmm1,0x55 a07d: c5 f0 c6 d9 ff vshufps xmm3,xmm1,xmm1,0xff a082: 62 f3 75 28 03 d1 07 valignd ymm2,ymm1,ymm1,0x7 a089: c5 fa 58 c1 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm1 a08d: c5 fa 58 c4 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm4 a091: c5 f0 15 e1 vunpckhps xmm4,xmm1,xmm1 a095: c5 fa 58 c4 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm4 a099: c5 fa 58 c3 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm3 a09d: 62 f3 7d 28 19 cb 01 vextractf32x4 xmm3,ymm1,0x1 a0a4: c5 fa 58 c3 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm3 a0a8: 62 f3 75 28 03 d9 05 valignd ymm3,ymm1,ymm1,0x5 a0af: c5 fa 58 c3 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm3 a0b3: 62 f3 75 28 03 d9 06 valignd ymm3,ymm1,ymm1,0x6 a0ba: 62 f3 7d 48 1b c9 01 vextractf32x8 ymm1,zmm1,0x1 a0c1: c5 fa 58 c3 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm3 a0c5: c5 f0 c6 d9 55 vshufps xmm3,xmm1,xmm1,0x55 a0ca: c5 fa 58 c2 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm2 a0ce: c5 f0 c6 d1 ff vshufps xmm2,xmm1,xmm1,0xff a0d3: c5 fa 58 c1 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm1 a0d7: c5 fa 58 c3 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm3 a0db: c5 f0 15 d9 vunpckhps xmm3,xmm1,xmm1 a0df: c5 fa 58 c3 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm3 a0e3: c5 fa 58 c2 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm2 a0e7: 62 f3 7d 28 19 ca 01 vextractf32x4 xmm2,ymm1,0x1 a0ee: c5 fa 58 c2 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm2 a0f2: 62 f3 75 28 03 d1 05 valignd ymm2,ymm1,ymm1,0x5 a0f9: c5 fa 58 c2 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm2 a0fd: 62 f3 75 28 03 d1 06 valignd ymm2,ymm1,ymm1,0x6 a104: 62 f3 75 28 03 c9 07 valignd ymm1,ymm1,ymm1,0x7 a10b: c5 fa 58 c2 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm2 a10f: c5 fa 58 c1 vaddss xmm0,xmm0,xmm1The first part similarly used vector instructions to compute 16 values at a time. But folding 16 results was even more complex and expensive, involving

vshufps,valignd,vunpckhps,vextractf32x4,vextractf32x8, etc. This additional complexity canceled out the gains from processing 16 dimensions per iteration, which explains why AVX-512 was slower.

(2) Why was naive float L2sq slower than naive high-precision L2sq under AVX-512?

Theoretically, high-precision L2sq should be slower because of float→double conversions. So why was it faster?

Looking at the disassembly of l2sq_naive_f64:

000000000000a280 <_ZL19l2sq_naive_f64PKfS0_m>:

a280: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

a284: 48 85 d2 test rdx,rdx

a287: 74 37 je a2c0 <_ZL19l2sq_naive_f64_oncePKfS0_m+0x40>

a289: c5 e0 57 db vxorps xmm3,xmm3,xmm3

a28d: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

a28f: c5 e9 57 d2 vxorpd xmm2,xmm2,xmm2

a293: 0f 1f 44 00 00 nop DWORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

a298: c5 e2 5a 04 87 vcvtss2sd xmm0,xmm3,DWORD PTR [rdi+rax*4]

a29d: c5 e2 5a 0c 86 vcvtss2sd xmm1,xmm3,DWORD PTR [rsi+rax*4]

a2a2: c5 fb 5c c1 vsubsd xmm0,xmm0,xmm1

a2a6: 48 83 c0 01 add rax,0x1

a2aa: c5 fb 59 c0 vmulsd xmm0,xmm0,xmm0

a2ae: c5 eb 58 d0 vaddsd xmm2,xmm2,xmm0

a2b2: 48 39 c2 cmp rdx,rax

a2b5: 75 e1 jne a298 <_ZL19l2sq_naive_f64_oncePKfS0_m+0x18>

a2b7: c5 eb 10 c2 vmovsd xmm0,xmm2,xmm2

a2bb: c3 ret

a2bc: 0f 1f 40 00 nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]

a2c0: c5 e9 57 d2 vxorpd xmm2,xmm2,xmm2

a2c4: c5 eb 10 c2 vmovsd xmm0,xmm2,xmm2

a2c8: c3 ret

a2c9: 0f 1f 80 00 00 00 00 nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]

- The code is much shorter than the float version.

- Although it includes scalar float→double conversions (

vcvtss2sd) and computes one dimension at a time, it avoids the complex and costly 16-element horizontal folding.

In other words, even with the conversion overhead, the simpler scalar path was still faster than the float version with vector folding. The compiler likely chose the conservative scalar path here, avoiding vectorization.

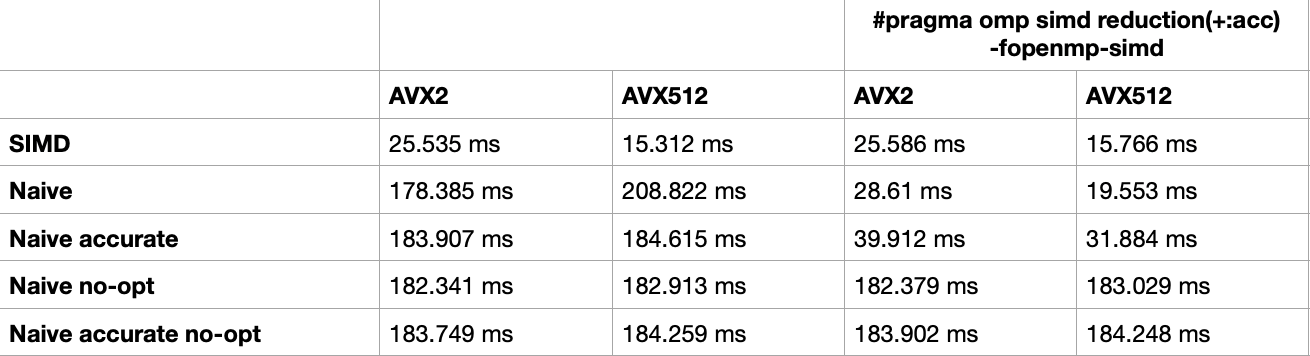

(3) How to Improve Naive L2sq for Better Compiler Vectorization?

The reason for horizontal folding is likely that the compiler strictly follows IEEE 754 semantics, preserving the exact order of floating-point additions. This prevents the compiler from reordering additions into vectorized accumulations.

To relax this, we can explicitly allow reassociation:

static inline double l2sq_naive_f32(const float* a, const float* b, size_t n) {

float acc = 0.f;

#pragma omp simd reduction(+:acc)

for (size_t i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

float d = a[i] - b[i];

acc += d * d;

}

return (double)acc;

}

And compile with -fopenmp-simd to enable this directive.

Running again shows a significant improvement: compiler auto-vectorization now achieves performance close to manual SIMD implementations. Using -ffast-math also works.

3. Summary

- SIMD significantly improves distance computation performance.

- Hand-written SIMD implementations perform best.

- For naive implementations, allowing reassociation (via

#pragma omp simd reduction(+:acc)or appropriate subsets of-ffast-math) is the key to approaching hand-written SIMD performance. Under strict IEEE semantics, the compiler conservatively generates per-iteration folding, which creates slow paths where AVX-512 does not necessarily have an advantage.