The previous 2 blog posts introduced MySQL’s locking mechanisms for insert and locking read operations.

Deep Dive into MySQL - Transaction lock - PART 1

Deep Dive into MySQL - Transaction lock - PART 2

In this post, we will discuss an optimization for locking during insert operations: implicit locks. We will cover their implementation, benefits, and the trade-offs involved.

Table of Contents

- What is an Implicit Lock?

- Implicit Lock Determination for Primary Key Records

- Implicit Lock Determination for Secondary Index Records ⭐️

- Worst-Case Scenario for Secondary Index Record Implicit Lock Determination ⭐️

1. What is an Implicit Lock?

When a MySQL transaction inserts a record, it holds a row lock on that record until the transaction is committed. But how is this row lock implemented?

Each record in a B+Tree can be located using <page id, heap no>, where page id consists of <space id, page no>, identifying the data page within the data file, and heap no represents the record’s position within that page.

MySQL maintains a global lock hash table for transaction locks. The hash key is the page id, and the hash value contains all locked records on that page. Locks for different records within the same page are organized into a linked list and distinguished using heap no.

Acquiring a row lock involves inserting a record into the lock hash table. However, before inserting into the hash, the hash itself must be locked to ensure consistency. This introduces a performance bottleneck in high-concurrency insert scenarios, even when there are no conflicts between inserted records.

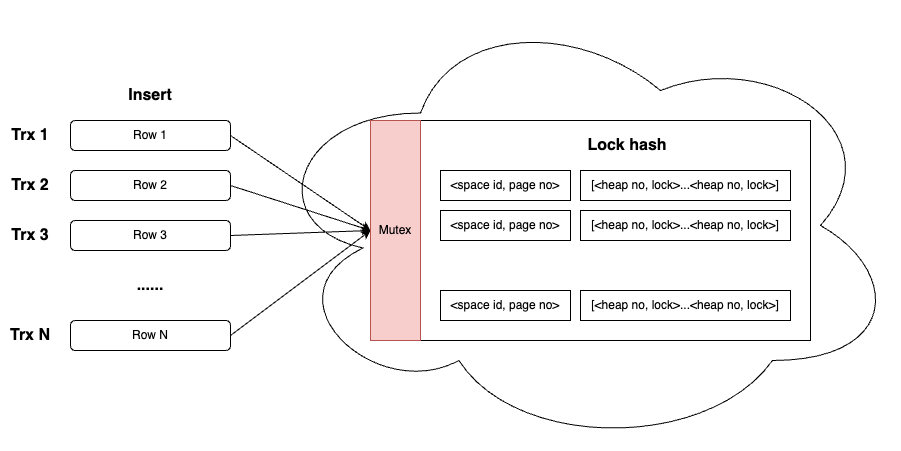

As illustrated below:

In this scenario, multiple concurrent transactions perform simple insert operations without conflicts. However, since each insert requires a row lock, they all contend for the global lock hash table, creating a performance bottleneck. (Partitioned lock hashes can alleviate this to some extent, but the problem remains.)

In this scenario, multiple concurrent transactions perform simple insert operations without conflicts. However, since each insert requires a row lock, they all contend for the global lock hash table, creating a performance bottleneck. (Partitioned lock hashes can alleviate this to some extent, but the problem remains.)

To address this issue, MySQL introduced implicit locks. Instead of registering row locks in the global lock hash table, insert operations leverage the record itself to express the lock state indirectly. This prevents concurrent insert operations from competing for the lock hash table. These implicit locks are automatically released upon transaction commit.

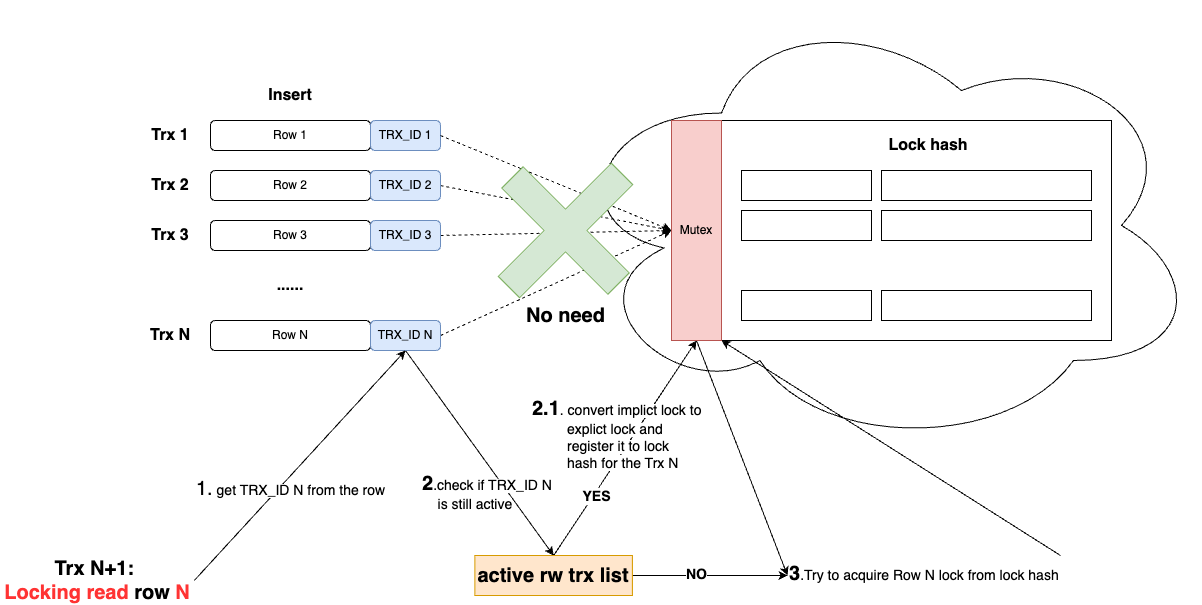

If another transaction accesses the inserted record before the transaction commits (e.g., through a locking read), it checks whether the record has an implicit lock. If an implicit lock is detected, this transaction converts it into an explicit lock, registers it in the lock hash table, and waits if necessary. If no implicit lock is found, it finally checks the lock hash table to determine if the record is locked.

Now, let’s explore how implicit locks are implemented in detail.

2. Implicit Lock Determination for Primary Key Records

The implementation of implicit locks for primary key records is straightforward. Each primary key record includes a hidden column, DATA_TRX_ID, which stores the transaction ID of the last operation (for inserts, this is the inserting transaction’s ID). Implicit locks leverage this transaction ID.

Each transaction is assigned a unique transaction ID when it starts. The DATA_TRX_ID of all inserted or modified records is set to this transaction ID. Additionally, MySQL maintains an active transaction list, which tracks uncommitted transactions. Once a transaction commits, its ID is removed from this list.

To determine whether a record has an implicit lock:

-

Retrieve the

DATA_TRX_IDfrom the record to get the transaction ID of the last insert/update operation. - Check if this transaction ID is present in the active transaction list:

- If not present, the transaction has already committed, so the record cannot have an implicit lock.

- If present, the transaction is still active, meaning the record has an implicit lock. In this case, convert it into an explicit lock and register it in the lock hash table.

- Attempt to acquire a lock on the record in the lock hash table. If another transaction already holds the lock, it must wait; otherwise, it acquires the lock successfully.

By introducing implicit locks, MySQL defers the costly operation of acquiring the lock hash mutex and registering row locks. This only happens if another concurrent transaction attempts to access the record. If no other transaction accesses the record, it avoids the lock hash operation entirely, improving concurrency for pure insert workloads.

Benefits and Trade-offs

- Benefit: Insert operations no longer need to register explicit locks in the lock hash table. Instead, explicit locks are registered only when another transaction tries to access the record.

- Trade-off: If a concurrent transaction tries to lock the record before the inserting transaction commits, it must check whether the

DATA_TRX_IDis still active, incurring additional overhead.

Fortunately, for primary key records, this overhead is minimal because:

- The

DATA_TRX_IDis readily available on the primary key record. - MySQL optimizes

trx_sysoperations to reduce the cost of checking whether a transaction ID is still active (though brief locking oftrx_sysmay occur).

However, implicit lock determination for secondary index records is much more expensive. Let’s examine why.

3. Implicit Lock Determination for Secondary Index Records

Implicit lock determination for secondary index records is costly because:

- Unlike primary key records, secondary index records do not have a

DATA_TRX_IDfield. - Instead,

DATA_TRX_IDexists at the page level, representing the transaction ID of the last insert/update operation on that page.

The implementation of implicit lock determination for a secondary index record in MySQL is quite complex. Before diving into the details, let’s first go over some essential background information about secondary indexes:

- As mentioned earlier, secondary index records do not have a hidden field for

DATA_TRX_ID; this information is only available at the secondary index page level. - Secondary index updates do not generate undo logs, meaning they do not support multi-versioning (MVCC) like primary key records. To locate the corresponding version of a secondary index record, it is necessary to first access the corresponding primary key record and then traverse its historical versions.

- The insertion/update sequence always processes the primary index before the secondary index. This means that for any given secondary index record, the primary key record version it points to must be either the same version or a newer version than itself.

- Updates to secondary index records are handled by marking the old record with a delete mark and inserting a new record.

To determine whether a secondary index record’s transaction has committed, we must rely on the page-level DATA_TRX_ID:

- If the page’s

DATA_TRX_IDcorresponds to a committed transaction, the secondary index record definitely does not hold an implicit lock. - If the page’s

DATA_TRX_IDis still active, we must locate the corresponding primary key record and check its transaction status. - Since primary key records maintain multiple versions (undo logs), finding the corresponding version can be expensive.

Step 3 is the most intricate part of the process. To understand how to accurately determine the corresponding primary key record version for a given secondary index record, we can refer to the following 8 representative cases.

Example Table Definition:

CREATE TABLE `tbl` (

`pk` int NOT NULL,

`value` int NOT NULL,

`sk` int NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (`pk`),

KEY `sk` (`sk`)

)

In the following 8 cases, we aim to identify the corresponding primary key record version for the secondary index record <10, 1>. By corresponding, we mean the specific version of the primary key record that resulted in the creation of the given secondary index record.

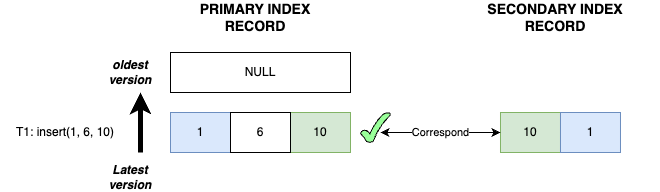

Case 1

- Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both inserted.

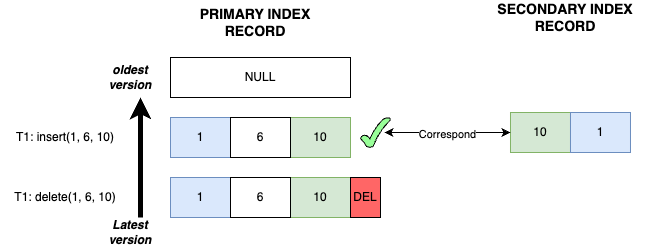

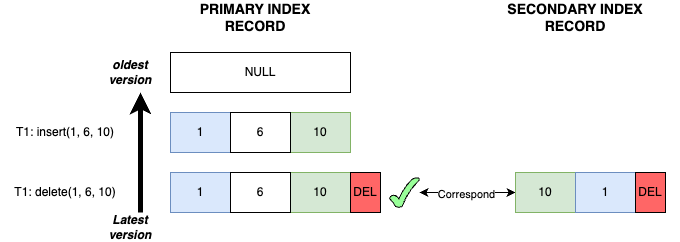

Case 2

- Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both inserted. - Transaction T1 deletes record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>generates a historical version and is marked with delete mark, but the secondary index recordS<10, 1>has not yet been marked.

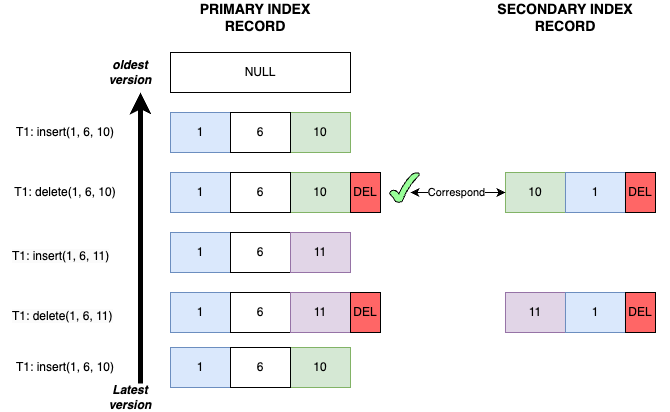

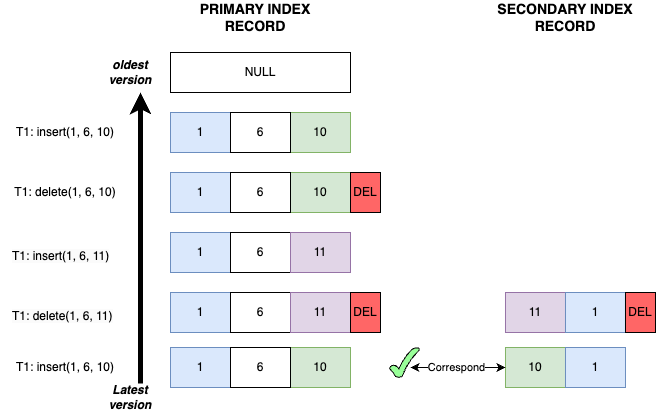

Case 3

- Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both inserted. - Transaction T1 deletes record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both marked with delete mark.

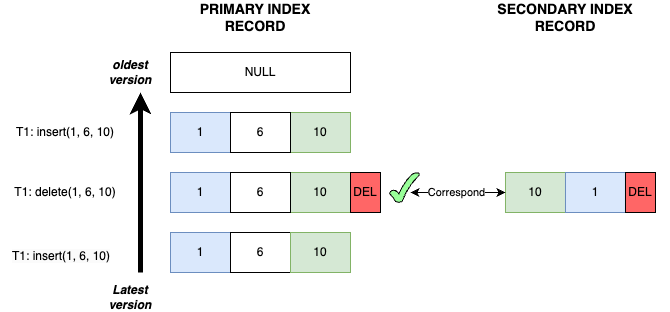

Case 4

- Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both inserted. - Transaction T1 deletes record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both marked with delete mark. - Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>is inserted, but the secondary index recordS<10, 1>has not yet been inserted.

Case 5

- Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both inserted. - Transaction T1 deletes record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both marked with delete mark. - Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both inserted again.

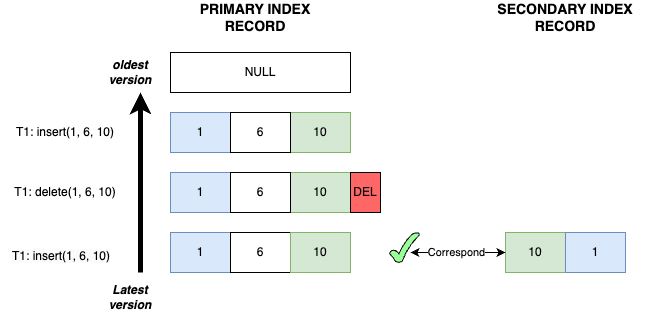

Case 6

- Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both inserted. - Transaction T1 deletes record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both marked with delete mark. - Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 11): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 11>is inserted. Whether the secondary index recordS<11, 1>is inserted or not is irrelevant in this case (since we only focus onS<10, 1>).

Case 7

- Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both inserted. - Transaction T1 deletes record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both marked with delete mark. - Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 11): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 11>and the secondary index recordS<11, 1>are both inserted. - Transaction T1 deletes record

(1, 6, 11): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 11>and the secondary index recordS<11, 1>are both marked with delete mark. - Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>is inserted, but the secondary index recordS<10, 1>has not yet been inserted.

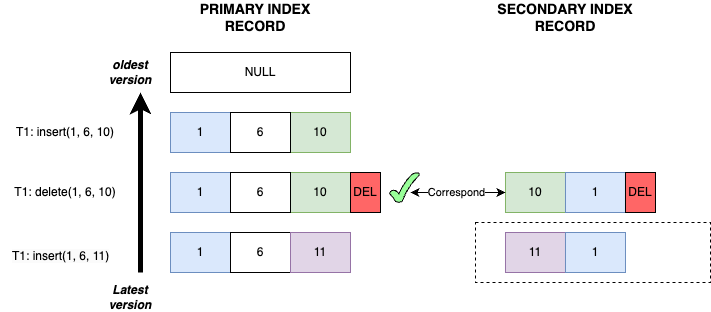

Case 8

- Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both inserted. - Transaction T1 deletes record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both marked with delete mark. - Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 11): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 11>and the secondary index recordS<11, 1>are both inserted. - Transaction T1 deletes record

(1, 6, 11): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 11>and the secondary index recordS<11, 1>are both marked with delete mark. - Transaction T1 inserts record

(1, 6, 10): The primary key recordP<1, 6, 10>and the secondary index recordS<10, 1>are both inserted.

The above 8 cases clearly illustrate how to determine the corresponding primary key record version for a given secondary index record. Once the correct primary key record version is identified, we can extract its DATA_TRX_ID field to precisely determine whether the secondary index record currently holds an implicit lock.

Summary of InnoDB’s Core Approach to Finding the “Corresponding” Primary Key Record Version for a Given Secondary Index Record:

- If the secondary index record does not have a delete mark, start from the previous version of its associated latest primary key record and traverse backward until the first non-matching primary key record version is found. The next version after this point is the corresponding version of the secondary index record.

- If the secondary index record has a delete mark, start from the previous version of its associated latest primary key record and traverse backward until the first matching primary key record version is found. The next version after this point corresponds to the delete operation of the secondary index record.

Definition of “Matching”:

A primary key record (or its historical version) P is considered matching a secondary index record S if:

Pdoes not have a delete mark, and- The value of the secondary index field in

Pis exactly the same as that inS.

Why Not Start from the Latest Primary Key Record Directly?

Since the search process involves traversing backward until a version meeting specific criteria is found, the next version after the stopping point is the target version. Thus, the stopping version cannot be the latest version. This serves as a small optimization by eliminating one unnecessary comparison.

Additionally, it is not always necessary to traverse all the way back to find the “corresponding” primary key record version. If, during traversal, the transaction ID of a primary key record version changes, it indicates that the previous transaction has already committed. Consequently, the secondary index record cannot have an implicit lock, and the traversal can be terminated early.

InnoDB’s implementation follows this approach, with the key function being row_vers_impl_x_locked_low(). Once you understand the explanation above, the actual code implementation becomes much easier to comprehend.

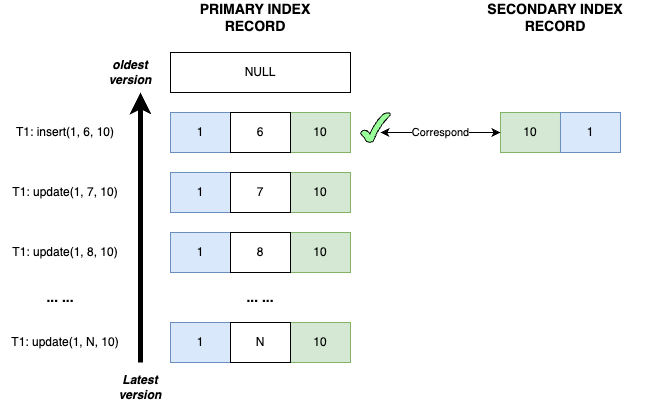

4. Worst-Case Scenario for Determining Implicit Locks on Secondary Index Records

From the implementation details discussed earlier, we can see that determining whether a secondary index record holds an implicit lock relies on traversing the historical versions of its corresponding primary key record. Based on this approach, we can construct a worst-case scenario where this determination process becomes extremely costly:

- Transaction T1 inserts record (1, 6, 10), where both the primary key record P<1, 6, 10> and the secondary index record S<10, 1> are inserted.

- T1 remains uncommitted and continuously updates the non-index field of this record, changing it as follows: (1, 6, 10) → (1, 7, 10) → (1, 8, 10) → (1, N, 10).

In this scenario, since only a non-index field is being updated, the secondary index record S<10, 1> remains unchanged. Additionally, based on the earlier definition of “matching”, all versions of the primary key record are considered matching the secondary index record.

According to the search approach described earlier, in order to find the corresponding primary key record version for S<10, 1>, the system must traverse all historical versions until it encounters the first non-matching version. In this case, that would require traversing back to the very first version. If N is particularly large, the cost of this backward traversal can be extremely high.

Thus, while implicit locks improve concurrency for insert operations, they also introduce a potentially significant overhead when determining implicit locks for secondary index records.

“There’s no free lunch.”