pgvector brings vector similarity search capabilities to the PostgreSQL. Thanks to PostgreSQL’s flexible extension architecture, pgvector can focus purely on implementing the vector index: defining the vector data type, implementing index operations like insert, search, and vacuum, managing index page and tuple formats, and handling WAL logging. PostgreSQL handles the rest — index file and page buffer management, MVCC, crash recovery, and more. Because of this, pgvector is able to implement its vector index at a low level, on par with PostgreSQL’s built-in nbtree index.

This is one of the key differences from MariaDB’s vector index. Due to MariaDB’s pluggable storage engine architecture and engineering trade-offs, its vector index is implemented at the server layer through the storage engine’s transactional interface. The storage engine itself is unaware of the vector index — it just sees a regular table. Curious about the internals of the MariaDB vector index? Take a look at my previous posts here[1] and here[2].

pgvector supports two types of vector indexes: HNSW and IVFFlat. This post focuses on the HNSW implementation, particularly its concurrency control mechanisms — a topic that has received relatively little attention.

1. Key Interfaces

-

hnswinsert: This is the core interface for inserting into the index. Its implementation closely follows the HNSW paper, aligning with the INSERT, SEARCH-LAYER, and SELECT-NEIGHBORS-HEURISTIC algorithms (Algorithms 1, 2, and 4). One difference I noticed is that pgvector omits the extendCandidates step from SELECT-NEIGHBORS-HEURISTIC.

-

hnswgettuple: This is the search interface. It invokes GetScanItems to perform the HNSW search, which aligns closely with Algorithm 5 (K-NN-SEARCH) from the paper. In iterative scans, GetScanItems not only returns the best candidates but also retains the discarded candidates — those rejected during neighbor selection. Once all the best candidates are exhausted, it revisits some of these discarded candidates at layer 0 for additional search rounds. This continues until hnsw_max_scan_tuples is exceeded, after which the remaining discarded candidates are returned as-is and the scan ends.

- hnswbulkdelete: This is the vacuum-related interface. It’s the heaviest part of pgvector, involving three steps:

-

Scanning all index pages to collect invalid tuples.

-

RepairGraph, the most complex step, removes invalid tuples from the graph and their neighbors, then repairs the graph to ensure correctness. This requires scanning all pages again and performing multiple search-layer and select-neighbors operations.

-

Safely deleting the invalid tuples from the index, again requiring a full scan of all pages.

As you can see, the full traversal of index pages three times plus extensive HNSW operations make this function very heavy.

-

- hnswbuild: This handles index creation. It uses the similar logic as hnswinsert, but with PostgreSQL’s index build APIs. Notably, it supports concurrent builds. Initially, it builds the index in memory; only when the memory limit is exceeded does it flush pages to disk and switch to on-disk insertions. WAL logging is disabled throughout the build phase.

2. Concurrency Control

In an earlier post, I analyzed the concurrency control design of MariaDB’s vector index. There, read-write concurrency is supported through InnoDB’s MVCC, but write-write concurrency is not.

pgvector goes further by supporting true write-write concurrency. Let’s dive into how pgvector handles concurrency between hnswinsert and hnswbulkdelete.

It introduces multiple lock types:

-

Page Locks These are PostgreSQL’s standard buffer locks and are used to protect individual pages. Pages in pgvector fall into three categories:

-

Meta Page: Stores index metadata.

-

Element Pages: Store index tuples.

-

Entrypoint Page: A special element page containing the HNSW entrypoint.

-

- HNSW_UPDATE_LOCK is a read-write lock used in pgvector to protect critical sections that span a larger scope than a single page lock.

-

Most inserts (hnswinsert) acquire it in shared mode, allowing concurrent inserts.

-

If an insert needs to update the entrypoint, it upgrades to exclusive mode to ensure only one insert can modify the entrypoint. hnswbulkdelete briefly acquires and immediately releases the lock in exclusive mode after collecting invalid index tuples and just beforeRepairGraph, ensuring that all in-flight inserts have completed. Otherwise, concurrent inserts might reintroduce the invalid elements being removed, making them neighbors again.

-

- HNSW_SCAN_LOCK Similar to HNSW_UPDATE_LOCK, but used to coordinate between hnswbulkdelete and hnswgettuple.

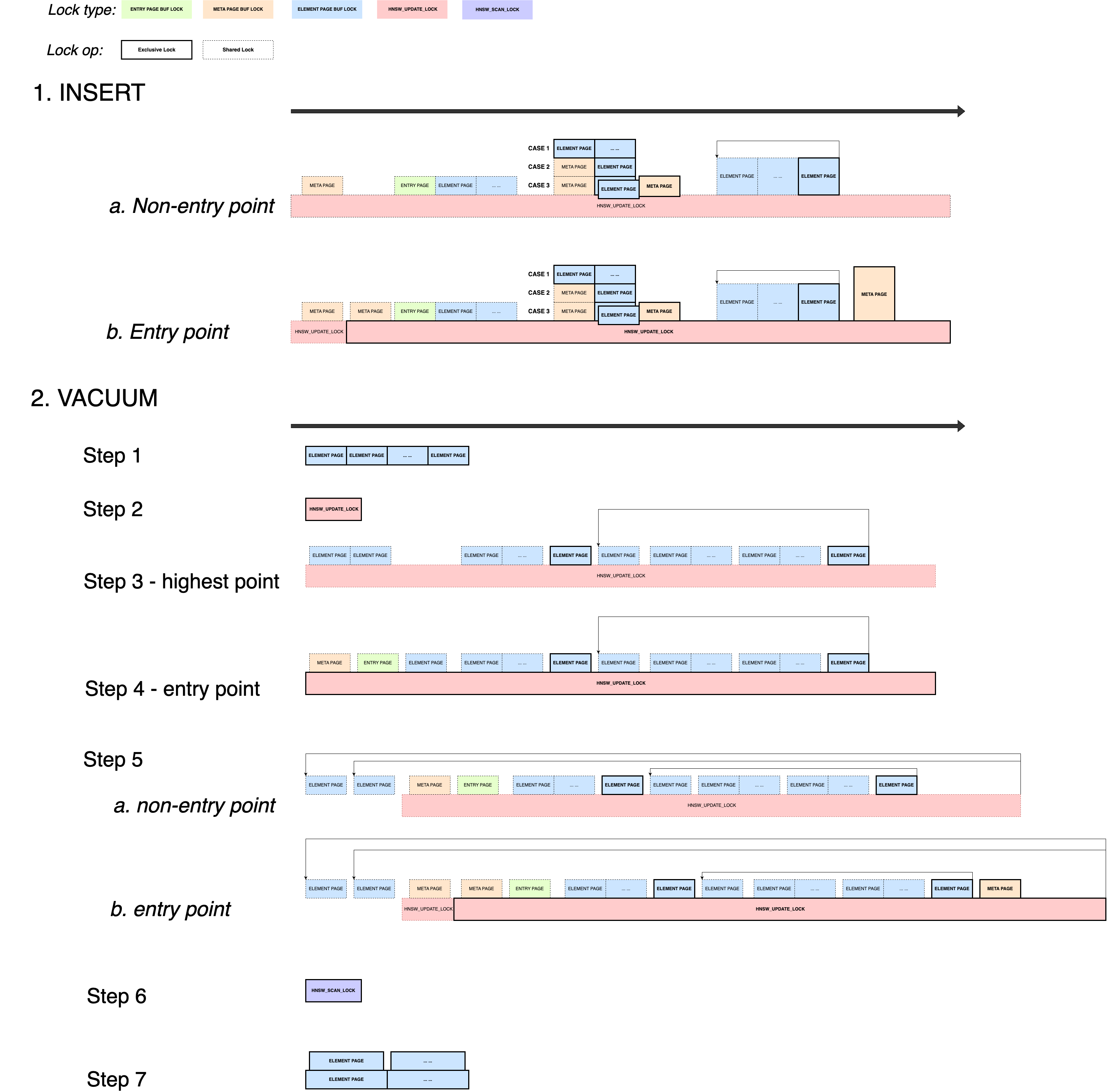

All locking operations in hnswinsert and hnswbulkdelete are well-structured. The diagram below shows detailed lock scopes in both implementations, where solid lines indicate exclusive locks and dashed lines indicate shared locks. I won’t go into all the details here — I may write a separate post covering the implementation specifics — but the diagram clearly illustrates that exclusive HNSW_UPDATE_LOCK usage is infrequent. Most operations acquire it in shared mode and hold short-lived page locks only as needed, keeping contention low.

What about deadlocks? The answer is simple: as shown in the diagram, in most cases only one page buffer lock is held at a time, eliminating the risk of circular dependencies. In rare cases, both an element page and one of its neighbor pages (also an element page) may be locked simultaneously. However, since pgvector maintains a globally unique current insert page, even these scenarios remain safe.

What about deadlocks? The answer is simple: as shown in the diagram, in most cases only one page buffer lock is held at a time, eliminating the risk of circular dependencies. In rare cases, both an element page and one of its neighbor pages (also an element page) may be locked simultaneously. However, since pgvector maintains a globally unique current insert page, even these scenarios remain safe.

3. Summary

pgvector is another textbook example of how to integrate vector search into a traditional OLTP database. Its implementation is elegant, closely aligned with the original HNSW paper.

Compared to MariaDB’s vector index, it stands out for its fine-grained concurrency control. However, it lacks the SIMD-level optimizations that MariaDB has introduced for better performance.

A deeper comparison between pgvector and MariaDB’s vector index internals would be an interesting future topic.

If you’re interested in performance benchmarks comparing pgvector and MariaDB, Mark Callaghan did detailed tests, check them out here.